If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Casetext was clearly on to something with its CARA brief-analysis software.

Not only did the American Association of Law Libraries name it 2017 product of the year, but it also spawned other brief-analysis products — Clerk from Judicata (reviewed here) and, just last month, EVA from ROSS Intelligence (reviewed here).

Now there is another. Launching today is Attorney IO, an artificial intelligence-driven application into which an attorney feeds a legal document such as a brief or memorandum and receives back suggestions of other relevant cases not mentioned in the document.

Now there is another. Launching today is Attorney IO, an artificial intelligence-driven application into which an attorney feeds a legal document such as a brief or memorandum and receives back suggestions of other relevant cases not mentioned in the document.

Its website promises to find “stunningly relevant” cases:

Every time you submit a document, our AI reviews millions of legal cases in order to unearth important patterns and connections. Then, the AI laser targets the cases that are most relevant to your document.

This sounds to be essentially the same as CARA, which also allows you to upload a brief or memorandum and find relevant cases not mentioned in the document.

Attorney IO is being launched by Alexander Stern, a 2015 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, and now an attorney in San Francisco.

“Lawyers of all skill levels can simply click on their legal documents to upload them to the AI,” says a press release announcing the company. “Then, the AI compares them to millions of cases. This process is analogous to a human legal researcher spending many lifetimes in law school in search of the cases most relevant to the submitted document.”

The service offers a 10-day free trial, after which it costs $299 a month. The company says it will offer free and low-cost options to pro bono attorneys.

Casetext offers CARA at $139 a month. EVA from ROSS is free.

Giving It A Try

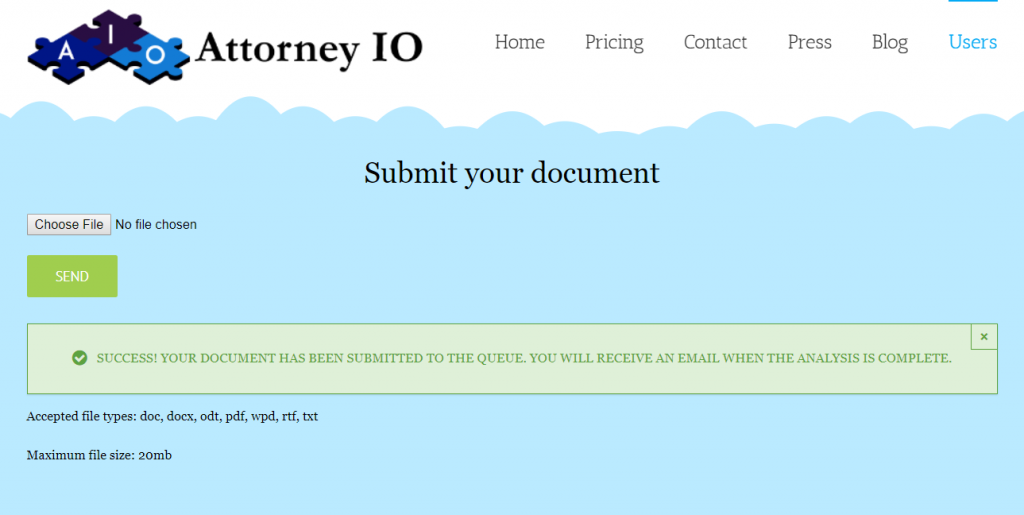

I gave it a quick try today, submitting a brief I’d recently filed as amicus curiae in an appellate matter. I registered for the free trial and then uploaded the brief.

After the upload, I got the message, “Success! Your document has been submitted to the queue. You will receive an email when the analysis is complete.”

Ninety minutes later, the email arrived. It informed me that the analysis was complete and said, “There are multiple ‘clusters’ associated with your document. These clusters represent different groupings of responsive case law. Thank you.”

The email contained two of these “clusters.” The first listed four cases and the second listed three cases. No explanation was provided of what these clusters meant or the subject they pertained to. There was simply a list of cases and citations. They were not linked to the case text.

As I read the cases, I could begin to understand the groupings of the clusters, as each pertained to an issue in my brief. I would say that the cases it suggested were all relevant to my brief, in that they all pertained to the issues addressed. Those in the first cluster were all cases I had already been aware of but chose not to use because there were other cases more directly on point. Those in the second cluster included two cases I had not considered in my research, but their relevance was fairly remote and I would not have used them in any event.

In fairness, my brief involved a fairly specific issue of state law and a related issue of statutory interpretation. The “universe” of cases pertaining to these issues is fairly narrow.

Bottom Line

Attorney IO’s website offers few details on the AI that underlies it. I don’t what happened during that 90 minutes that it was evaluating my brief. I wish the results had been better explained and that they had included links to the actual cases.

Generally speaking, I like brief-analysis applications as a means of double-checking a brief before filing or of quickly assessing an opponent’s brief. Since Attorney IO is free to try for 10 days, you can try it yourself with your own briefs and see what results you get.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog