The legal research platform Judicata will soon roll out a powerful tool that uses statistical insights to provide detailed analysis and grading of the strengths, weaknesses, thoroughness and drafting of briefs.

Judicata founder Itai Gurari describes the new tool, called Clerk, as moneyball for motions. “Just as different batters have different on-base percentages, different motions have different probabilities of being granted or denied,” Gurari wrote in a recent blog post.

Comparisons will inevitably be made between Judicata’s Clerk and CARA, the brief-analysis tool introduced last year by Casetext that finds cases that are relevant to a legal document but not cited in it. However, Clerk goes well beyond CARA, not only identifying missing cases but also analyzing the strength of a brief’s citations and arguments in granular detail and suggesting ways to improve them.

How It Works

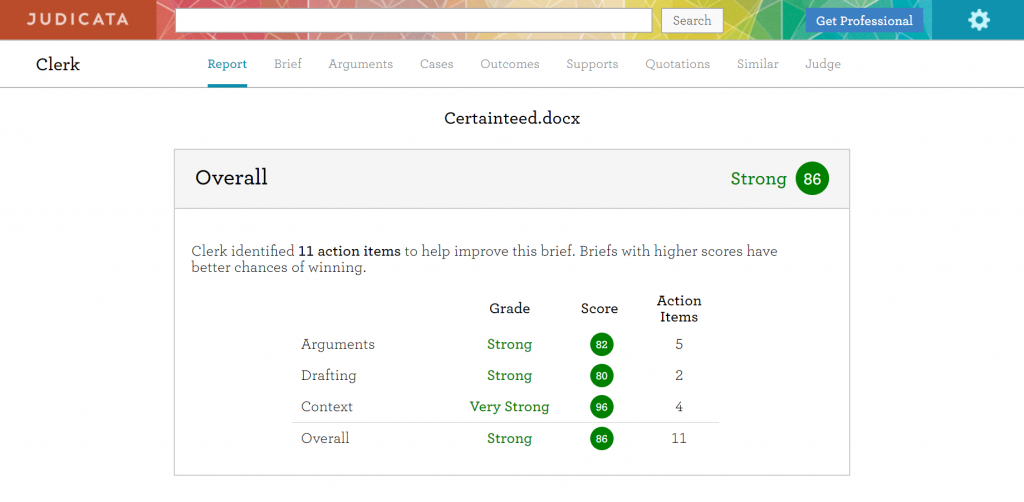

Upload a brief to Clerk in either .DOCX or .PDF format, and it presents you with a report assigning an overall grade, an analysis of strengths and weaknesses, and recommended action items to improve the brief. The first tab of this report is a high-level summary that analyzes:

- Arguments. This tells you whether cases referencing similar arguments as your brief generally rule for plaintiffs or defendants, whether the cases you’ve cited are vulnerable to attack, and the ratio in your brief of defendant-winning to plaintiff-winning cases.

- Drafting. This tells you how well your brief does at supporting its legal principles with strong cases and how good a job it does of correctly citing and attributing quotations.

- Context. This gives you an outcome breakdown of similar cases based on the same cause of action and procedural posture and also with regard to the specific judge who will decide your motion.

“What we do here is give the lawyer a quick glimpse of the main things to check out here,” Gurari told me during a recent demonstration. “We want them to go deeper.”

(See a working demo of Clerk here.)

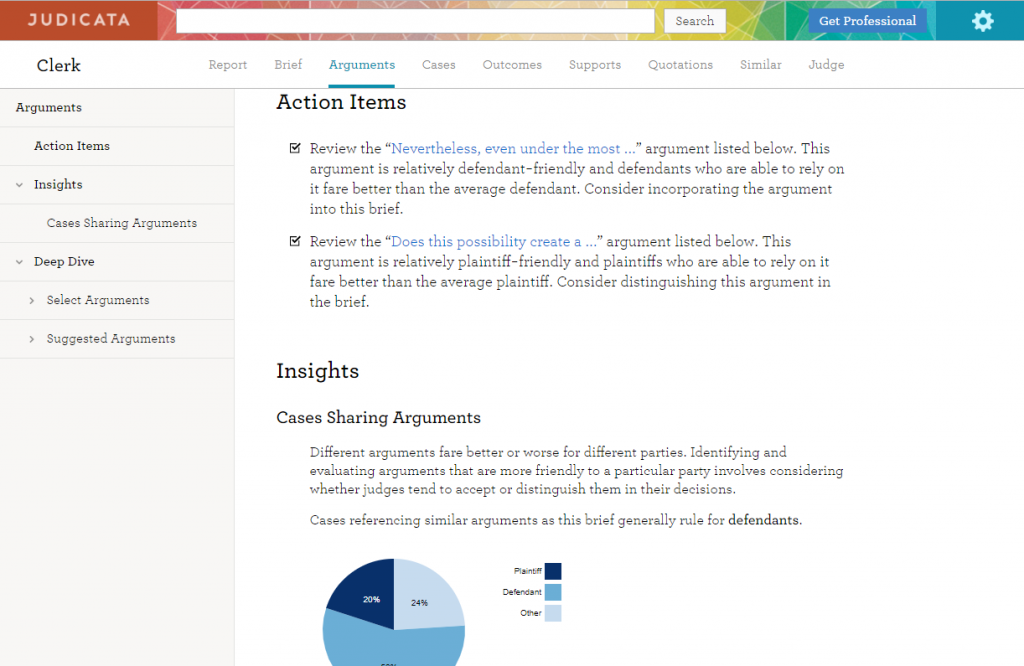

The Arguments tab includes suggested action items and insights on how to better support the arguments within a brief.

And deeper you can go. By clicking through a series of eight additional tabs, the lawyer can find detailed information that can be used to refine the lawyer’s own brief or analyze an opponent’s brief:

- Brief. This tab shows the brief with text highlighted to indicate sections that can be improved with additional cases or edited to fix incorrectly quoted citations.

- Arguments. This tab evaluates the arguments presented in the brief and suggests others for consideration. The premise is that different arguments fare better or worse for different parties and that by identifying and evaluating arguments that tend to go one way or the other, the brief can be made stronger. This report extracts key arguments from the brief and analyzes relevant cases for the side they support. It also suggests additional arguments based on their favorability to one side or the other.

- Cases. This tab assists with understanding the citability and precedential value of the cases relied upon in the brief. It lists the cases you’ve cited and analyzes their vulnerability, on the premise that winning briefs tend to rely on fewer vulnerable cases. “One of the key components of a strong brief is citing to cases that are less subject to attack, as opposed to trying to distinguish cases that are more vulnerable,” Elisabeth Hoover, product manager at Judicata, explained during the demonstration.

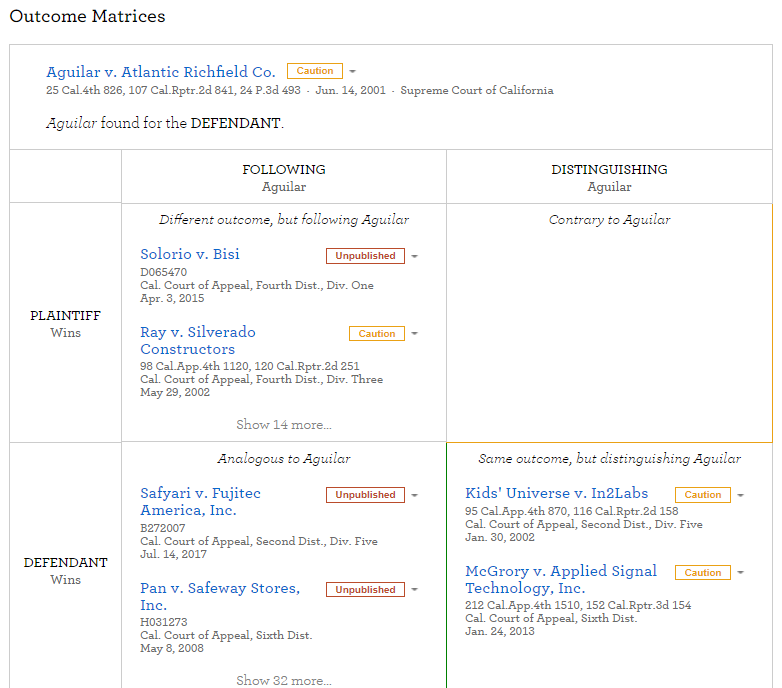

- Outcomes. This tab identifies the outcomes of the cases cited within the brief and assists in achieving a good balance. Judicata’s statistics demonstrate that both plaintiffs and defendants fare better when they cite to more cases that go their way. This report analyzes the ratio of plaintiff-winning to defendant-winning cases in your brief (or vice versa) and then provides a deeper dive into each of the cases. It also presents Outcome Matrices for the cases in your brief that suggest other cases that support them, categorizing them by which party won and whether they followed or distinguished the case you’ve cited.

- Supports. This tab assists with finding the best supporting cases for the legal principles in this brief. For each principle, it analyzes the strength to which cases support that principle based on factors such as cause of action, posture, outcome and citability.

- Quotations. This tab checks the accuracy of quotations to cases and statutes cited in the brief. Judicata has found that winning briefs make fewer quotation errors. This report finds missing, changed or added language in quotations and incorrectly cited page numbers.

- Similar. This tab provides insight into appellate decisions involving similar cases, including those with the same cause of action and posture as the brief. The idea is that by helping attorneys understand the outcomes of similar cases, they will be better equipped to hone their own arguments.

- Judge. This tab provides context about the judge the brief is filed with and appeals from their decisions. Statistics analyze who appeals the judge’s decisions and how they fare on appeal, to identify whether the judge is more friendly to plaintiffs or defendants.

Objectively Evaluate A Brief

Judicata’s analysis of briefs to date has found that winning briefs tend to score higher in Clerk than losing briefs and also tend to do better across all the individual components, meaning they use fewer vulnerable cases, have a better ratio of cases that go their way, and have fewer quotation mistakes.

“We want to bring an understanding that there’s an objective way to evaluate a brief, but it all links back to best practices,” Gurari said. “The goal is not to say you should score this or that, but to help you better understand how your document stacks up and what the numbers indicate about it.”

It would be impossible for a researcher to manually look at and analyze all the cases that pertain to a given issue, Gurari notes. There could be thousands of cases and many would turn out to be irrelevant. But a computer can do it in seconds.

“We try to give you both the forest and trees perspectives,” Gurari said. “We do all the grunt work to find all this caselaw but we also try to tell you what it means, what you can do to improve your brief.”

For now, the forest is limited to California. As I reported last May, Judicata recently came out of several years of stealth mode to unveil what it had promised would be “a better legal research service.” Although Gurari hopes eventually to expand to other jurisdictions, Judicata currently covers only California civil cases and statutes.

The key to what distinguishes Judicata from other research platforms is its ambitious effort to “map the legal genome” — that is, to map the law with extreme accuracy and granularity. While that has been a time-consuming effort stretching back over several years, it is what has enabled the company to launch Clerk with so high a degree of statistical granularity, Gurari said, and it is what will enable Judicata to roll out other innovative products and features going forward.

Judicata will offer Clerk as a standalone product, separate from its research service, for which it offers both free and paid versions.

A live demo of Clerk, analyzing an actual filed brief, can be seen here.

My Thoughts

I am always reluctant to make too strong of a pronouncement about a product until I’ve had a chance to put it through the paces first-hand. I have not directly used Clerk, but I have seen the demo I mentioned above and also a second demo, and I was given an in-depth walk through by Gurari, product manager Elisabeth Hoover, and lead engineer Benjamin Pedrick.

My sense is that Clerk is a true game changer for California attorneys. Judicata’s statistics bear out what all lawyers already know as a matter of common sense: Briefs with strong arguments and strong cases in support of those arguments will fare better than briefs with weaker arguments or that rely on more vulnerable cases.

Clerk is moneyball for motions, as Gurari said, applying statistical and machine learning analysis to evaluate the relative strengths and weaknesses of arguments and cases in briefs so that lawyers can adjust their strategies accordingly. Clerk is not a guarantee of success for any given brief. But it can improve your odds of success and maybe help you be more successful overall.

Moneyball works in sports. Why can’t it also work for law?

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog