In August, the Silicon Valley-based international law firm Gunderson Dettmer became one of the first U.S.-based firms — if not the first — to develop and launch a “homegrown” internal generative AI tool, which it calls ChatGD.

As Joe Green, the firm’s chief innovation officer, told me at the time, “Given our position as a firm that focuses exclusively on working with the most innovative companies and investors in the world, we thought it would be really worthwhile for us to get our hands dirty and actually get into the technology, see what we can do with it.”

Now, more than four months into it, the firm is beginning to get a clearer picture of just what it can do with the technology — and what it cannot. It has also had a chance to track adoption of the technology among the firm’s professionals, see how they use it, and measure the cost to the firm of providing this proprietary AI.

In a LinkedIn post today, ChatGD: Learnings (So Far) from our Legal GenAI Experiment, Green provides an update on the firm’s deployment of AI. Yesterday, in advance of the post, I had the opportunity to speak with Green and John Scrudato, Gunderson’s senior legal engineering and data strategy manager. They provided additional details on the experience so far and shared updates on new features they are launching today.

Half the Firm Has Used It

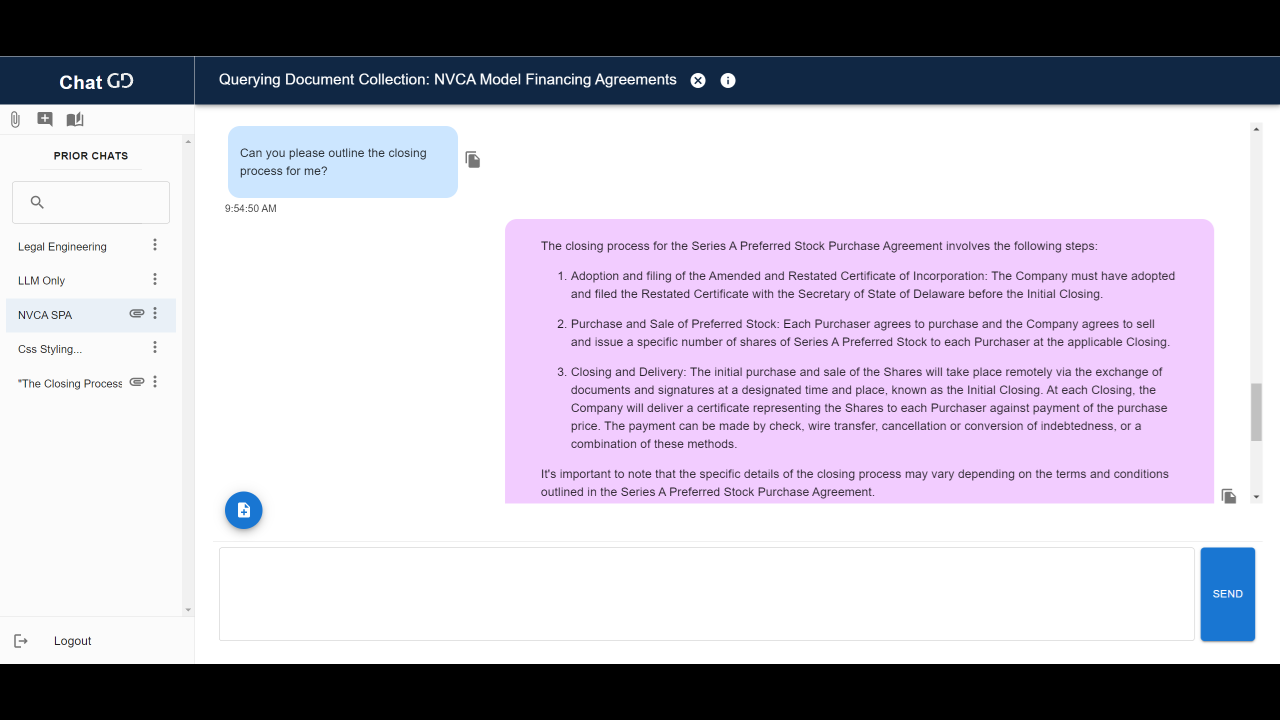

By way of a refresher, the firm launched ChatGD with two main components. One is a general chat mode, similar to ChatGPT, where attorneys can directly have conversations with the large language model (LLM). The other component allows users to query their own documents using retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), a method of using relevant data from outside the LLM to augment queries.

Using this RAG component, lawyers can upload documents or collections of documents and then query the LLM and receive responses based on the context provided by the documents. Not only does this allow lawyers to query the LLM based on their own internal knowledge, but it also reduces hallucinations and increases accuracy, Green said.

Fast forward to today, and Green reports that nearly half the firm has already used ChatGD and that usage and engagement continue to steadily increase. Users have submitted and completed more than 9,000 prompts across several thousand conversation threads.

“For the lawyers and business professionals who have engaged with it, we’ve gotten some really wonderful feedback, including ways that they’ve figured out how to get really interesting results out of the tool,” Green told me.

Before anyone was allowed to use ChatGD, the firm required them to complete an initial training, either live or on demand. The firm presented three live training sessions tailored specifically for its attorneys, paralegals and business professionals. More than half the firm attended one of those three live trainings, which Green said is a testament to the high level of interest within the firm in GenAI generally and in the tool they built.

“We framed the rollout of ChatGD as a collaborative experiment designed to help everyone move up the learning curve and to crowdsource the most promising use cases and methods for getting the best results out of GenAI-powered tools,” Green writes in his LinkedIn post.

The focus of the trainings, which were developed by Scrudato and members of the firm’s AI Working Group, was on how LLMs and RAG actually work, in order to provide everyone with a baseline understanding of the technology, and how to use ChatGD safely and ethically. The trainings also covered the ideal use cases for generative AI and areas where the technology is not yet well suited.

Various – But No Surprising – Use Cases

Once people in the firm began to dive in to using ChatGD, they did so in a variety of ways, Green says.

“Our attorneys are using it to retrieve and manipulate or summarize language in legal agreements, draft and change the tone of emails, summarize documents and articles, and brainstorm different examples of legal language or topics for presentations,” he says.

It has also proven useful to the firm’s business and technology professionals. Green says they have used it to help create and repurpose content for marketing, answer RFPs, prepare for meetings, structure and format data, write code and improve written communications.

At the same time, Green said he has not seen any surprising or unanticipated uses of ChatGD, possibly in part because the trainings primed people to specific use cases.

“We gave some examples of ways that we suggested using the tool, and in our review of the results, it seemed like a lot of people were using it for that type of work, which was great — changing the tone of an email, taking text formatted in one way and turning it into bullets, summarizing short things, or things of that nature,” he told me.

But in one variation from the norm, one attorney, an early adopter of the tool who frequently uses it in his professional work, used it to write a birth announcement for his daughter, in the form of a parody of The Night Before Christmas.

A Surprise on Cost

Perhaps the most surprising highlight of the deployment so far has been the cost. Fear of the cost of commercial and enterprise LLMs has inhibited some law firms from rushing into adoption or broad deployment of generative AI.

Joe Green

But Green projects that the total annual cost to Gunderson for providing ChatGD to the entire firm will be less than $10,000 — a figure he calls “staggeringly low.”

“We had a sense that the cost differential between prices vendors were asking for their tools versus what we could do would be pretty meaningful,” Scrudato told me. “I was shocked at how much of a difference it really is.”

Even that $10,000 was mostly attributable to operational and infrastructure costs, not to the actual LLMs. (It does not include the firm’s internal engineering.)

Green, in his post, attributes the firm’s ability to keep the cost that low to two strategic decisions:

- Self-hosting an open-source model for RAG vector embeddings.

- Leveraging GPT 3.5 Turbo for both pure chat and RAG functionalities instead of using the most expensive models available.

“I think that when a lot of people say LLMs are expensive, they’re talking about use cases where they’re processing enormous amounts of data, or possibly brute forcing something,” Scrudato said. “But if you’re just using it as a way to interact with the user, it’s quite economical, especially if you’re using a model like GPT 3.5 Turbo. It’s cheap, it’s not expensive.”

Updates Released This Week

This week, Gunderson released major updates to ChatGD, which Green describes in his LinkedIn post.

Using prompt-routing and open source embeddings models, the firm has constructed multiple indices that employ a combination of keywords, knowledge graphs, vector embeddings and autonomous retrieval to dynamically optimize the chosen fact retrieval method for a user’s specific prompt as part of our RAG workflow.

That includes routing prompts to different LLMs for fact retrieval and summarization to perform the language generation step of the RAG process, allowing the firm to use larger context windows and larger models for better summarization while reserving more cost-effective models for fact retrieval.

For especially detailed summarization tasks, ChatGD routes the requests to the most powerful models with the largest context windows to provide the model with full context of the source material.

“We’re using prompt routing as sort of an entry point from a given prompt to decide what tools to actually use to respond to their question,” Scrudato explained.

“So if someone says, ‘I want a detailed summary of this document,’ we can essentially have the LLM decide that this requires a larger context window and a more powerful model, and route that to a GPT-4 32,000 token context window model, which is a much heavier, more expensive model.

“For a lot of interactions, you don’t need that much power, but for some, it makes a lot of sense. So a lot of the work we’ve done is behind the scenes in letting us respond dynamically to people’s requests based on their intent, and then pick the right tool, the right LLM, to help them achieve what they want to do.”

As of now, the firm is using three different foundational models as part of ChatGD’s tech stack, and deploying the best available model for each particular purpose. The firm has also made a number of user experience and performance enhancements based on user feedback, and it is prepared to upgrade its fact-retrieval LLM to GPT 4 Turbo as soon as it becomes available to for production use.

Assessing the Experiment

Given that Gunderson embarked on developing this tool as a sort of an experiment, I asked Green to summarize the results so far and what he has learned.

“The experiment is definitely ongoing,” he said. “The current results: We have learned a tremendous amount ourselves through the process of building this application that I think will make us much more savvy consumers of the technology in this space — to be able to see what really involves a significant amount of engineering and a significant added value above what the foundational models are capable of doing.”

He said that it has been exciting to see how people are using it and for what use cases.

“But to get to the higher value use cases without another kind of step change in the capabilities of the technology — which I’m not discounting will come — but to get to those higher value use cases, a significant amount of additional engineering is going to be required to make it consistent and high quality enough that it can be done in a production environment with the kind of stakes that a law firm has.”

Both Green and Scrudato said it has also been useful to understand what is possible with the technology.

“When we see products that do seem to be doing something truly different, truly unique, or they put in a lot of engineering time, that’s interesting to us,” Scrudato said. “Whereas I think we’re better able to spot a product that, as some people have kind of been saying recently, a lot of products are just thin wrappers on ChatGPT, and I think we’re pretty readily able to identify those products and make good buying decisions.”

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog