Slated to launch next month is a service that allows consumers to get answers to their legal questions by text for a flat price of $20.

The service, called Text A Lawyer, is modeled after ride-sharing service Uber in that it uses two separate mobile apps, one for consumers to submit legal questions and another for lawyers who are in a waiting pool ready to give answers.

The goal, says founder Kevin Gillespie, is to make it simple for low- and moderate-income consumers to get answers to legal questions. Text-messaging is a medium many are comfortable with, he says, and it has the added advantage of providing both the consumer and lawyer with a transcript of the Q&A.

Gillespie plans to launch the service next month, initially only in Oregon and Washington and only for landlord/tenant issues. He plans to expand the service nationwide, but is looking for investors to help fund the marketing and advertising he will need to do that.

How It Works

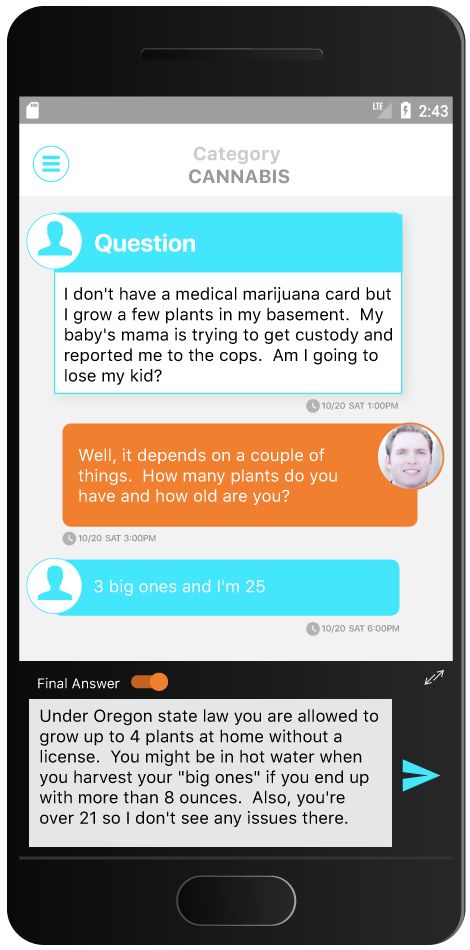

Consumers will pay $20 to submit a legal question. After consumers open the app, it prompts them to select the state in which they reside and the kind of lawyer they are looking for (family, criminal, immigration, etc.). It then asks them to describe their question in a few sentences. A final screen is a conflicts check, asking the names of any alleged victims, adverse parties and witnesses, and the consumer’s relationship to any of these people.

Within a minute or two, Gillespie says, the app will connect the consumer to a lawyer. In one final step before making the connection, the app asks the consumer to read and accept the attorney’s limited-scope engagement agreement.

Within a minute or two, Gillespie says, the app will connect the consumer to a lawyer. In one final step before making the connection, the app asks the consumer to read and accept the attorney’s limited-scope engagement agreement.

The consumer and lawyer are then connected in a secure, encrypted chat box where the lawyer can ask any questions to clarify the issue and then provide a final answer. Once the lawyer gives a final answer, the consumer’s credit card is charged and the consumer has two minutes to ask a follow-up question, for which the consumer will be charged $9. The number of follow-up questions is unlimited, but each will cost $9.

Text A Lawyer will send the question to the highest-rated lawyer who is currently online and who fits with the state and legal category. The app will clearly notify the lawyer of the incoming client, and the lawyer will have only a brief time to accept.

Once the consumer has no additional questions, the attorney swipes the Final Answer button on the app to indicate that the engagement is concluded. If the consumer and the attorney wish to extend the relationship outside the app, they are free to do so.

The attorney will receive an email with a transcript of the Q&A. The consumer can choose whether or not to receive the transcript. Gillespie says he made this option for consumers because some might be in a position where it would not be safe or confidential for them to have the transcript.

The communications are fully encrypted and Text A Lawyer does not store any of the information. As an added privacy measure, the company will do a nightly wipe of its servers to erase all Q&As.

Payments to Lawyers

The lawyer earns $15 of the initial $20 and $8 for each additional question. Text A Lawyer takes $5 of the initial fee — $4 for what it calls a connection fee and $1 for a software licensing fee.

Based on these fees, a lawyer who participates in the service could earn $150 an hour or more working from home, Gillespie says. Of course, that would depend on how much business the service generates and the time it takes to answer each question.

A frequent ethics issue lawyers face when considering participating in a service such as this is whether the fee to the company is inappropriate fee splitting. To avoid this issue, Text A Lawyer has come up with a novel approach.

Text A Lawyer processes payments through the payment-processing company Stripe. When a consumer submits a question, Stripe puts a hold on the consumer’s card but does not charge it until the lawyer indicates that the engagement is completed.

At the point of charging the consumer’s card, Stripe separates the $20 so that $15 goes to the lawyer and $5 goes to Text A Lawyer. The two payments are never commingled, the lawyer pays nothing to Text A Lawyer, and there is no retainer paid by the client. The payment to the lawyer is a fixed fee for services already rendered.

As noted, users of the app must agree to a limited-scope, limited-engagement agreement before they can submit a question. Text A Lawyer will provide a model engagement agreement, but each participating attorney will be able to tailor the agreement to his or her own specifications, and the consumer will be required to agree to that attorney’s agreement before being connected.

Lawyer Ratings

After each session, the consumer is asked to rate the lawyer on a scale of 1-5. The ratings are not made available to the app’s users, but are used by Text A Lawyer to assign lawyers. When multiple attorneys are available in the waiting pool, the highest-rated lawyer will always be assigned first.

This becomes a self-culling system, Gillespie says. Lawyers who are poorly rated will end up spending a lot of time in the waiting pool with no business. Sooner or later, they will quit the app because they are not making money.

“This ensures the marketplace rewards the lawyers who answer questions to the satisfaction of their customer and pushes the others aside,” Gillespie says.

To protect the consumers who use the app, lawyers who sign up for the pool must verify their bar admission. Thereafter, each time they log in to the app, attorneys will be required to take a selfie and submit it to Text A Lawyer as verification of identity. Text A Lawyer will do a daily scan of bar disciplinary pages and deactivate any lawyer who has been disbarred or suspended.

Ethics Considerations

Gillespie says that he has worked with a national law firm to make the service compliant with the rules of professional responsibility in almost every state. He has come up with a couple of creative ways to protect lawyers who use the service.

One is the payment-processing system described above. Another is the system to help avoid conflicts of interest. As noted, consumers must fill out a brief conflict-of-interest form. Once the attorney is selected for connection to the consumer, the attorney is able to review this conflicts form.

For lawyers who are users of the Clio practice management platform, the Text A Lawyer app will automatically run the conflicts check through Clio.

This happens before the consumer is asked to agree to the attorney’s engagement agreement. If the attorney finds a conflict, the attorney can reject the assignment.

Even after accepting a matter, an attorney can always reject it based on discovery of a conflict of interest. The app also allows attorneys to reject matters at any time based on ethics grounds — such as a question seeking help in performing an illegal act — or based on the consumer having provided the wrong state or legal category. In the latter case, the attorney can forward the matter back into the correct pool.

The Bottom Line

Founder Gillespie says he was inspired to create Text A Lawyer while a student a Vermont Law School, after taking the legal hacktivist course taught by Jeannette Eicks, co-director of the school’s Center for Legal Innovation. Eicks is on Text A Lawyer’s advisory board.

His target customers are the lower 50 percent of America’s income bracket — those who cannot afford a lawyer. He believes that a for-profit model is the best way to serve this population, for the simple reason that lawyers do not work for free.

It is clear that he has put a lot of time and thought into developing a product that addresses the concerns of both consumers and lawyers. For lawyers, it is particularly noteworthy that he has made efforts to ensure compliance with ethics rules in most states — although he acknowledges there are still some problem states — and that he has come up with creative solutions to address concerns around fees, conflicts and engagement agreements.

He has also built into the service protections for consumers, including requiring verification of the lawyer’s identity upon each log-in, daily checks of bar disciplinary records, and assignment of attorneys based on consumers’ ratings.

He has so far bootstrapped the development out of his own pocket. His ability to take this to a broad market may turn on his ability to attract new investors — which, as I mentioned, he is actively seeking.

One obvious problem I foresee is that, while the app is designed for “simple” legal questions, consumers may have no clue whether their question is simple. Gillespie’s answer to that is that the lawyer answering the question can provide a brief response that explains the need for the consumer to consult with a lawyer for a more detailed response.

My take is that Text A Lawyer could be a win-win for consumers and lawyers. For consumers, it could allow them to get immediate answers to simple legal questions at low cost and with little hassle. For lawyers, it could provide a new income stream for those who work from home or are not currently working.

For a detailed demonstration of both the lawyer app and the consumer app, watch the video below:

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog