In video remarks that opened the second day of the Legal Services Corporation’s annual Innovations in Technology Conference in San Antonio last week, Bridget Mary McCormack, president and CEO of the American Arbitration Association and former chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court, urged attendees to engage in “radical collaboration.”

“AI alone won’t close the justice gap, but radical collaboration at this very moment can,” she said, emphasizing the importance of breaking down traditional silos. “If we can break down silos that traditionally separate courts, legal aid organizations, academia, technologists and dispute resolution providers, we can build a better future together.”

Thanks to weather delays, I was able to attend only one full day of this three-day conference. But in my brief time there, I heard McCormack’s “radical collaboration” theme echoed many times. I also heard multiple stories of legal services organizations (LSOs) executing on that theme – stories that described collaborations not only with other LSOs, but also with law schools, courts, bar foundations, law firms, and others – all with the goal of driving innovation and better serving their low-income clients.

Innovation Through Collaboration

The largest national funder of civil legal aid programs for low-income Americans, the LSC is an independent non-profit established by Congress in 1974. Through its Technology Initiative Grants (TIG) program, it is also the single-largest funder of technology innovation among LSOs, even though — as I discussed in some detail in a 2024 post — the total annual funding of the TIG program is just $5 million, a drop in the bucket compared to the funding getting poured into big law legal tech.

To no one’s surprise, much of the innovation talked about at this year’s ITC revolved around AI. While LSOs are using AI in various ways, one of the most talked about areas of AI development involved client screening and intake, with organizations using AI agents and voice agents to streamline this traditional bottleneck.

As Jane Ribadeneyra, the LSC’s senior program officer for technology, remarked during her overview of the most recent round of TIG grant awards, “Access to justice starts with access to intake.”

Ribadeneyra detailed several 2025 TIG grants focused on modernizing intake systems, including AI-powered applications from Florida Rural Legal Services and the Legal Aid Society of Middle Tennessee, which together partnered with Haven AI to build AI-powered hotline screening, and Southern Minnesota Rural Legal Services, which is integrating generative AI into Minnesota’s coordinated intake system.

But some of the most compelling AI discussions I heard at the conference centered not on individual organizational achievements, but on R&D efforts designed to maximize collaboration across organizations and prevent potentially costly mistakes.

Open, Collaborative R&D

Margaret Hagan, executive director of the Legal Design Lab at Stanford Law School, led a panel on a groundbreaking seven-state AI cohort she is helping coordinate that exemplifies the “radical collaboration” theme.

The cohort has brought together tech teams from LSOs in West Virginia, Ohio, Texas, Oregon, Minnesota, Illinois and Michigan, which are working together to avoid three major risks of working independently:

- Unsustainable patchworks, in which every organization tries to build its own version of an AI-powered intake system, but then those systems cannot be sustained because grants run out and systems breaking when models change.

- Poor performance and reputational harm, in which undertested AI tools get greenlighted but then do not perform well in the field, leading to bad headlines, regulatory inquiries and potential user harm.

- Missing the moment, in which initial funding grants lock organizations into poor-performing tech tools could squander this window of opportunity.

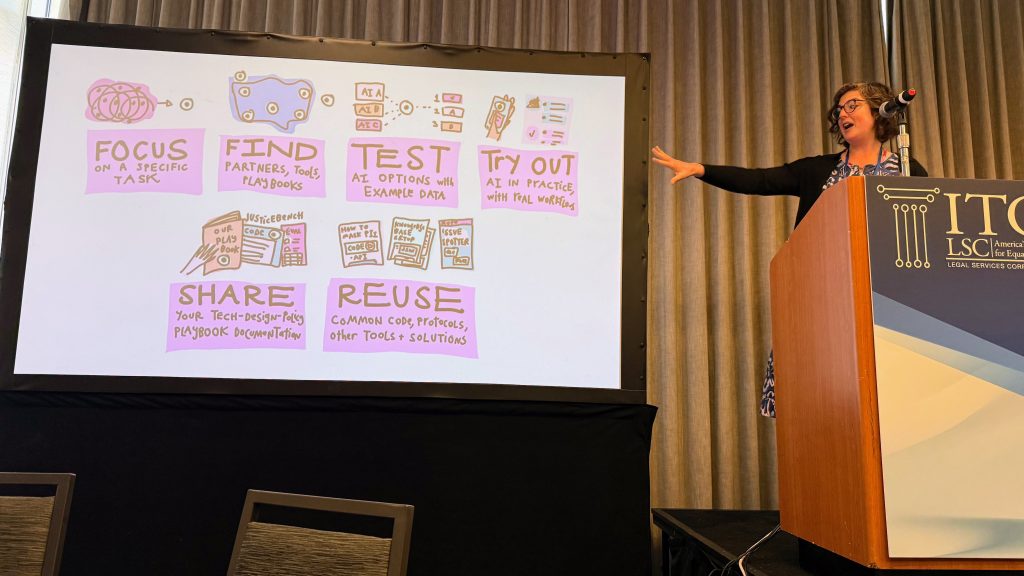

Rather than each organization independently developing AI tools, the cohort follows a structured R&D process and systematically shares the lessons they learn. Together, Hagan said, they are focusing on specific pain points, testing with shared datasets, piloting solutions with real users, and documenting everything at JusticeBench.org, an open R&D platform where anyone can build on existing work rather than start from scratch.

Margaret Hagan outlined the process being used by the legal services cohort she is coordinating, urging attendees to “be intentional” about how they choose the tech projects on which to focus.

One of the participants in that cohort, Matthew Keister, product manager at Ohio Legal Help, provided a detailed look at a driver’s license reinstatement tool the cohort had helped develop.

He discussed some of the technical lessons that any organization working on document analysis would need to learn, including that orientation detection matters, OCR errors are predictable and addressable, date hallucinations can be prevented, and lengthy documents need chunking.

The panelists emphasized the critical importance of knowledge bases – structured information about legal resources, services and rules. As Hagan emphasized, the “gold stuff” that legal organizations have is their expertise, and a key focus should be on structuring and labeling that expertise to make it AI-ready.

This collaborative approach was also evident during another program, in which Russ Bloomquist, full stack developer at Maryland Legal Aid, demonstrated a containerized, self-hosted AI platform his organization has developed. His organization’s executive team had mandated that any software they build should be shareable, he said, “because if it’s useful for us, it’s probably going to be useful for someone else.”

Maximizing What You Have

But beyond radical collaboration and cutting-edge AI, I could not help but be struck by a third theme that seemed dominant at this year’s conference. I can best describe it as “maximizing what you already have.”

Several programs on the agenda targeted this theme. One, for example, covered security measures every legal aid IT team can implement right now, without breaking the bank. Another, on hybrid approaches to access to justice, talked about how to blend new technologies with established practices.

Making better use of the technology they already have makes sense, given that LSOs typically do not have huge technology budgets to invest in building or buying new tech tools.

(In this regard, see my 2024 post, in which I wrote about the “legal technology justice gap” and the severe lack of funding for technology development and innovation in this sector.)

And while they may not have the budgets to expand their tech stacks, it is also true that many do not make full use of the technology they already have.

DLA Piper’s director of pro bono programs, Anne Helms (at podium) kicks off a panel on making better use of the tech tools you already have. Panelists were (from left): Vivian Hessel, CIO at Legal Aid Chicago; Elisabeth Cappuyns, director of knowledge management at DLA Piper; and Jon Quist and Erin Lettire from Microsoft.

That point was driven home by one panel I attended, “Knowledge Management Without AI: Using the Tools You Already Have.” Moderated by Anne Geraghty Helms, director and counsel for U.S. Pro Bono Programs at DLA Piper, the panel brought together voices from big law, legal aid and Microsoft.

The idea for the panel came about, Helms explained, when she had initially approached her firm’s legal aid partners with an offer to provide cutting-edge AI training, only to receive polite pushback.

What organizations really wanted, she learned, was training on how to use some of the tech tools that were already at their disposal and that they were already paying for.

The Real Challenges

Setting the stage for that panel, Vivian Hessel, chief information officer at Legal Aid Chicago, outlined five interconnected challenges that plague legal aid organizations, none of which require new technology to solve:

- Change management is perhaps the most fundamental obstacle, she said. Technology gaps persist “when people don’t have time to explore and learn and just try new things.” The challenge intensifies because LSOs often work with systems – intake systems, email platforms, reporting tools and collaboration software – that are not well integrated.

- Email overload is a universal pain point, with email having become the default for everything: document storage, project management, communication, and collaboration. “That’s inefficient and that makes collaboration difficult,” Hessel said.

- File search inefficiency compounds the email problem. Files scatter across case management systems, inboxes, shared folders and personal folders.

- Reluctance to share work in progress reflects the very human challenge of people’s hesitancy to share unfinished work, fearing they will invite feedback that creates more work when they are already overwhelmed with cases.

- Concerns about AI and transcription tools present a newer challenge, with legal professionals wanting assurance that client data is protected and that tools are being used ethically and responsibly.

None of these challenges stem from lack of commitment, Hessel emphasized. “We know everybody is working extremely hard in very complex settings.” Rather, they reflect the reality of under-resourced organizations operating with disconnected tools.

Practical Solutions with Existing Tools

Building on those challenges, two panelists from Microsoft, Erin Lettire, senior technical program manager, legal operations, and Jon Quist, director supporting Microsoft’s Corporate, External, and Legal Affairs organization, demonstrated concrete applications of widely available tools, primarily focused on SharePoint. The duo walked through several practical applications:

- Structured data intake using Microsoft Forms and SharePoint Lists to capture all necessary information upfront, minimizing repetitive back-and-forth communication.

- Task and request management through SharePoint Lists can offer huge advantages over email, with the ability to assign work, track status, add priority flags and create a searchable history of how similar situations were handled.

- Collaborative document creation can solve the problem of version control. The key, they said, is creating a single source of truth by being intentional about where documents are first saved – saving directly to OneDrive for Business or a SharePoint site folder instead of local hard drives, then sharing links rather than email attachments.

- Content discovery and metadata can allow organizations to move beyond paper-based folder hierarchies. By using custom metadata columns instead of folders, organizations can view content across dimensions that folders cannot support.

Rounding out the panel, Elisabeth Cappuyns, director of knowledge management at DLA Piper, provided broader context for how these tools fit into a KM framework. A former corporate lawyer who switched to KM, she said that it is simply about helping lawyers practice smarter and avoid the need to reinvent the wheel.

She described practical applications at DLA Piper, including the firm’s creation of a central knowledge platform using SharePoint Online, and its repurposing e-discovery platforms to help pro bono clients organize self-help materials.

Cappuyns encouraged LSOs to leverage their law firm partners. “Please use us, your outside law firms, for either technology that you might not have or updated versions. But also for the experience that we have – we see a lot of tools, we use a lot of tools, and so we’re happy to consult with you on how to use them best.”

LSC’s Strategic Evolution

While the conference put a spotlight on the innovative work taking place at LSOs across the country, it also highlighted the LSC’s own commitment to collaboration and strategic technology development.

Selena Hunn, deputy director in LSC’s Office of Program Performance, detailed the 2024-2025 Technology Summit, a two-year process convened as part of LSC’s 50th anniversary, with the purpose of creating a blueprint for how technology can be more effectively leveraged to narrow the justice gap.

That process resulted in the recent publication of the Technology Summit’s report, The Next Frontier: Harnessing Technology to Close the Justice Gap.

The report contains seven recommendations, with perhaps one of the most significant, Hunn said, being to reframe technology as essential to the core mission – moving beyond viewing technology as merely operational to positioning it as central to grantees’ work in expanding access to justice.

(Watch for a separate post from me about this report.)

Three Converging Themes

Perhaps the key takeaway from the conference was that these three themes – radical collaboration, AI innovation and maximizing existing resources – are not separate strategies but interconnected approaches to closing the justice gap.

As McCormack said in her remarks: “It’s not about the tech so much as it is about culture, governance and trust. People need to know that we’re being thoughtful about where AI belongs and where it doesn’t.”

She cited examples of collaboration by the AAA, including an AI-driven debt diversion tool built for Lancaster County Court in collaboration with the National Center for State Courts and online dispute resolution tools for family court cases in Boston developed with Suffolk Law School.

“What connects these projects is the mindset,” McCormack said. “We’re not asking what can the AAA do, but rather what can we all do together that none of us can do alone.

“That shift from siloed innovation to radical collaboration is, in my view, the single most important change we need to make if we’re serious about closing the justice gap.”

Margaret Hagan’s AI cohort panel reinforced this message with four key takeaways for leadership:

- Be strategic, not reactive. Don’t chase every AI idea. Focus on specific tasks with proven pain points.

- Don’t start from scratch. Before building something new, find who else has worked on it.

- Invest in your knowledge base. The “gold stuff” legal organizations have is their expertise. Structure it, label it, and make it AI-ready.

- Share as you go. Practice “radical collaboration.” Share code, datasets, evaluation methods, and learnings so others can build on your work.

Looking Forward

Even based on my abbreviated time there, the conference offered evidence that LSOs are simultaneously pushing forward with cutting-edge AI development while also working to extract greater value from the tools they already have.

And, as evidenced by their very attendance at this conference, they are increasingly doing more of this through radical collaboration – sharing knowledge, coordinating R&D efforts, and breaking down silos among organizations, law firms, courts, academia and technology providers.

To quote McCormack one more time: “We all know that technology is not the goal. Better outcomes for people are the goal.”

The conference offered ample evidence that achieving those better outcomes is not a matter of choosing among collaboration, innovation and optimization – but rather of pursuing all three strategically and simultaneously.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog