In a redacted brief filed Nov. 19 with the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Thomson Reuters urged the court to affirm the Delaware district court’s ruling that ROSS Intelligence infringed Westlaw’s copyrights by copying thousands of its attorney-written headnotes to train an AI-powered legal research tool.

“Copying protectable expression to create a competing substitute isn’t innovation: it’s theft,” the brief asserts. “This basic principle is as true in the AI context as it is in any other.”

The 85-page brief (which you can read here), signed by Kirkland & Ellis partners Dale Cendali, Joshua Simmons and Miranda Means, defends the copyrightability of Westlaw’s headnotes, the editorial summaries written by its attorney-editors, and portrays them as a hallmark of creative legal analysis rather than mere factual summaries.

“For over a hundred years and as recently as 2020,” TR’s brief argues, “the Supreme Court has upheld ‘the reporter’s copyright interest in explanatory materials including headnotes.” Citing Callaghan v. Myers (1888) and Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org (2020), TR calls headnotes “a paradigmatic example of protectable material,” and argues that the Delaware court was right to treat 2,243 of them as copyrightable works.

TR asserts that its headnotes are crafted through numerous creative editorial choices — how to phrase the point of law, how many headnotes to create, which facts or concepts to include, which case passages to link and how to categorize them within the West Key Number System. These choices, TR says, easily satisfy the minimal creativity required by Feist.

ROSS, the brief says, “may want to ignore the Supreme Court’s numerous statements that headnotes are protectable, as it did in its opening brief, but this Court must follow binding precedent.”

‘Knew It Could Not Legally Access Westlaw’

TR’s account portrays ROSS as a commercial actor that knowingly copied Westlaw to build a rival product. After being denied a Westlaw license, ROSS allegedly hired the outsourcing firm LegalEase Solutions to scrape Westlaw data and convert headnotes into “question and answer” pairs for training its AI model.

According to exhibits described in the brief, LegalEase contractors “copied the West Headnotes into the form of questions” and then copied “the case passages that West’s attorney-editors had selected to link to those headnotes.” TR accuses ROSS of using bots to “scrape Westlaw en masse,” creating “thousands of Bulk Memos quickly” and copying “hundreds of thousands of annotated cases.”

(Two days before using ROSS in 2020, TR settled litigation against LegalEase based on similar facts, with the two parties agreeing to entry of a consent judgment and stipulated permanent injunction in the U.S. District Court in Minnesota.)

The brief asserts that ROSS used the resulting material multiple times in training its AI system. It cites testimony that ROSS already possessed a repository of case law but needed Westlaw’s editorial analysis to build a functional search tool capable of mapping natural-language questions to relevant case passages.

ROSS’s conduct, TR contends, was not inadvertent: “ROSS knew it could not legally access Westlaw. When ROSS directly asked TR for a Westlaw subscription, TR expressly declined.” Yet after learning this, the brief says, ROSS induced first another company (whose name is redacted) and then LegalEase to get ROSS access anyway.

‘A Direct Substitute, Not a Transformative Use’

On the question of fair use, TR’s central argument is that ROSS’s platform “substituted for and competed with Westlaw in the legal research platform market.”

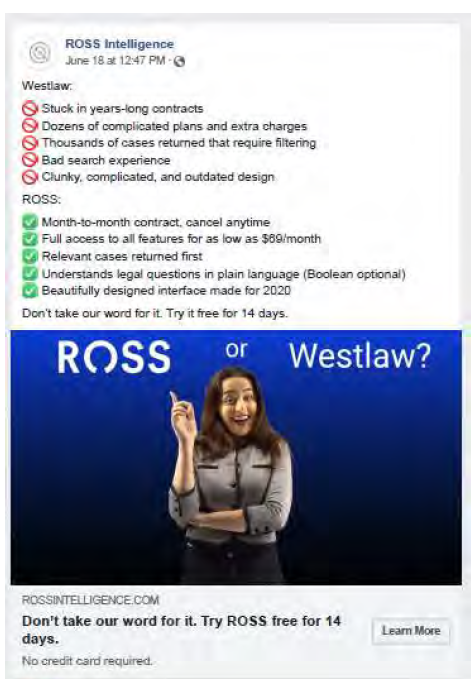

It says ROSS’s marketing materials explicitly positioned its AI as a “Westlaw replacement,” even using slogans like “ROSS or Westlaw?” alongside a price comparison ad — a copy of which is reproduced in the brief.

Under the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, TR says, ROSS’s use was not “transformative” because it served “the same purpose as the original,” which was to “help researchers find and understand the law.”

It draws a contrast with other cases, such as one involving Google Books, which merely indexed books and drove users back to the originals.

See all my coverage of this litigation here.

Here, it contends, ROSS “copied the Westlaw content that already provided a way for researchers to find and understand law to develop a competing way to find and understand law.”

TR also accuses ROSS of acting in bad faith, noting a similar case in which the court found bad faith when the defendant “requested a license, was refused one, and then obtained a copy from a third party rather than paying the requisite fee.”

That, it says, “is precisely what happened here, where ROSS was refused a license and then illicitly went through a third party.”

Harm to Westlaw’s Markets

Much of TR’s brief focuses on market harm, which it argues is the most important of the fair use factors. It argues that ROSS’s copying deprived TR of several valuable markets:

- The existing market for Westlaw subscriptions.

- The potential market for licensing Westlaw content as AI training material.

- The exclusive ability to train its own AI using that content.

“ROSS harmed the original market for Westlaw by substituting therefor,” TR argues, and it “diminished the value of the Westlaw content by depriving TR of its exclusive ability to train its own AI on that content.”

A ruling in ROSS’s favor would have broad consequences, the brief argues. “If any competitor could copy the Westlaw content to train their own legal research platform, why on earth would anyone pay TR for it?”

AI Innovation or ‘Parasitic Copying’?

Responding to arguments from ROSS and others that enforcing TR’s copyright in this case would hinder AI progress, TR suggest that is alarmist, pointing out that Westlaw itself has used artificial intelligence “long before the founders of ROSS were in school.” The company cites milestones from its own AI history dating back to the 1990s, including its 1992 launch of the “first commercially available search engine with probabilistic rank retrieval” and the 2018 launch of WestSearch Plus, an AI-powered research feature.

“AI development has moved forward at a rapid pace since the decision below was entered, and will surely continue to do so,” the brief says.

While there may be scenarios where training an AI algorithm using copyrighted material is fair use, “this scenario — where the copying was for purposes of creating a commercial substitute for the original — is not one of them.”

The brief’s concluding paragraph drives home the theme that ROSS’s behavior is not about innovation but misappropriation:

“This case may involve AI, but it is far from novel. ROSS indisputably pilfered the creativity of a competitor to bring to market a substitute. ROSS’s copying was not technological advancement. It was theft.”

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog