Unless you have been living in a cave for the past two years, you are undoubtedly aware of the rash of AI hallucination cases plaguing the legal profession. These are cases in which lawyers-who-should-know-better file briefs they’ve generated using AI without ever checking the citations, only to learn — surprise of surprises — that the AI made up some of the citations.

While 2023’s Mata v. Avianca is the most infamous of these cases, its wayward lawyers were merely the first of a long line. According to AI Hallucination Cases, a site maintained by HEC research fellow Damien Charlotin to track these cases, there have been at least 160 cases to date involving hallucinated case citations.

Now, legal technology company LawDroid is making it easy for lawyers to protect themselves against needless monetary sanctions and ruined reputations.

It has launched CiteCheck AI, a site where lawyers can verify the citations in a document, absolutely free. Well, free up to a point. I’ll get to that in a moment.

Related: LawDroid Founder Tom Martin on Building, Teaching and Advising About AI for Legal.

The way it works is so simple that any lawyer can do it. Simply upload a brief (or other legal document) in either Word or PDF format, and CiteCheck AI goes through a four-step process:

- Document Analysis Step: Extracts citations using OpenAI GPT models and Google Vision OCR.

- Database Verification Step: Cross-references with CourtListener legal database.

- Similarity Analysis Step: Performs 80% confidence threshold matching.

- Quality Assurance Step: Final verification with complete audit trails.

“While AI tools from major Legal AI vendors and frontier models offer assistance, Stanford research shows they may generate fabricated citations up to 88% of the time,” said Tom Martin, CEO of LawDroid “With CiteCheck AI’s professional grade citation validation, lawyers now have no excuses for citing hallucinated cases. Every lawyer needs to be using this!”

Trying It Out

I signed up and gave it a try. I started by uploading the very filing that got the lawyers in trouble in the now famous case of Mata v. Avianca.

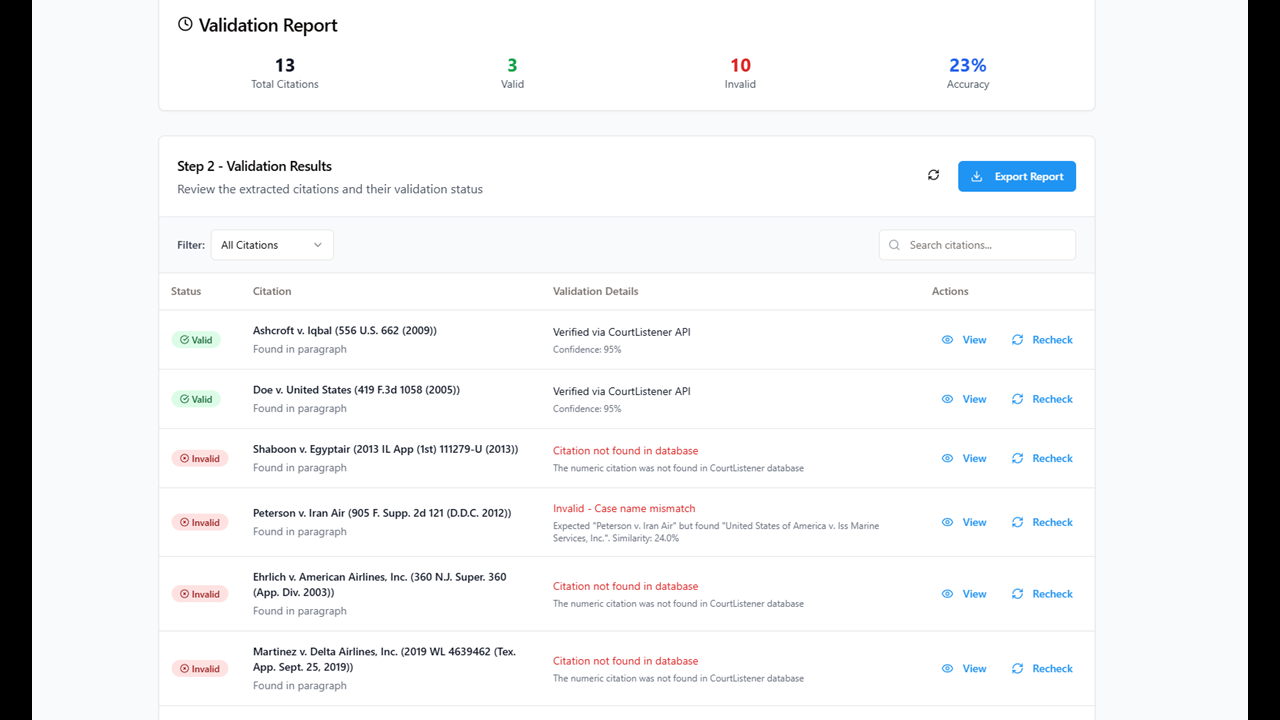

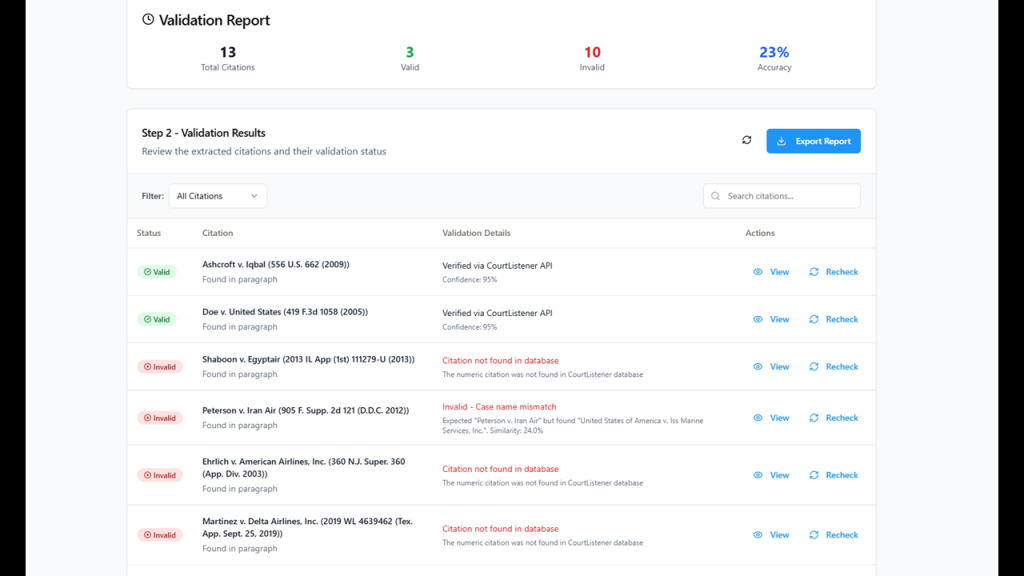

CiteCheck took about 50 seconds to analyze the case. You can partially see the results in the image above. Sure enough, it identified all the hallucinated cases as invalid, in some cases because the citation could not be found, and in others because the case name did not match the citation.

CiteCheck took about 50 seconds to analyze the case. You can partially see the results in the image above. Sure enough, it identified all the hallucinated cases as invalid, in some cases because the citation could not be found, and in others because the case name did not match the citation.

In other words, had Mata’s lawyers used this tool, they might still be dwelling in relative obscurity.

I then tried it by uploading an actual appellate brief I had previously filed. But before I uploaded it, I sprinkled in a couple of fake citations using legitimate citation styles.

It took just over a minute for CiteCheck to review my Word document. A second try with a PDF document took about three minutes to perform both the OCR and cite checking.

Sure enough, it identified my made-up citations, flagging them in red as invalid, with the message, “Citation not found in database. The numeric citation was not found in CourtListener database.”

For citations it could validate, it flagged them in green as valid, with the notation, “Verified via CourtListener API” and a further notation showing the confidence level.

However, it did tag a number of citations as invalid, even though I know them to be valid.

For some cases, it could not validate them against the CourtListener database because they had only a Westlaw citation (e.g. 2004 WL 123456). For these cases, I got the same message as I did for the cases I had made up.

For other cases, it identified them as invalid because of a case name mismatch resulting from the use of abbreviations.

For example, my brief had the citation, Detroit Free Press Inc. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 829 F.3d 478 (6th Cir. 2016). CiteCheck tagged this as invalid because of a case name mismatch, and provided the note: “Expected ‘Detroit Free Press Inc. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice’ but found ‘Detroit Free Press Inc. v. United States Department of Justice’. Similarity: 71.7%.”

In my opinion, I am OK with those valid citations having been marked invalid, as I would rather err on the side of caution. In each case, it was the result of some inconsistency in citation style, and I would rather have a cite checking tool alert me to those issues than not. Had I used this for an actual filing, I would have caught the fake citations and been alerted to check the citations where the style might have been nonconforming.

Note also that, similar to the Descrybe cite checker that I wrote about earlier this week, CiteCheck AI does not check non-case citations. It will not check citations to statutes, regulations, law review articles, or other types of sources.

Free and Premium Pricing

CiteCheck is free to use for the first five validation reports. You will have to provide your name and email address, but no credit card is required to try it out.

After that, the service costs $25 a month for up to 100 reports or $100 a month for up to 500 reports.

Bottom Line

“The time for excuses has ended,” says LawDroid’s Martin. “Every legal professional now has access to transparent citation verification. The question isn’t whether you can afford this protection; it’s whether you can afford to practice without it.”

There’s no arguing with that point. Lawyers should be checking their cites before they file a brief. In my mind, that means they should be reading every cited source and ensuring that it is what they say it is. But as a final failsafe, a cite-checking tool such as LawDroid’s new CiteCheck AI should always be used.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog