Even free legal research platforms need to make money at some point, and so as Descrybe.ai today launches a paid upgrade, it is making it worth your while, offering a “Legal Research Toolkit” with a suite of features, including its own AI-driven citator, which it calls the Cytator.

As I wrote about Descrybe last year, it was founded by a Boston-area husband and wife team, Kara Peterson and Richard DiBona, whose own experience with the legal system inspired them to create a free legal research platform with the goal of democratizing access to legal information.

They used AI to generate summaries and abstracts of court opinions and make them searchable. Last October, they rolled out a major upgrade that included a redesign of its platform, more nuanced and accurate search results, summaries of judicial opinions in Spanish as well as English, and simplified, plain-language summaries in both English and Spanish.

Descrybe was also a finalist this year in the ABA Techshow Startup Alley that I oversee.

Descrybe will continue to offer a free version. Everything that was free remains free, Peterson told me. The paid upgrade it is introducing today adds a number of features that will make it a more attractive legal research option for legal professionals. These features, packaged as Descrybe’s Legal Research Toolkit, include:

- The Cytator. I will write more about this below.

- Brief Checker. Upload a brief — either your own draft or one you receive — and Descrybe will identify hallucinated, inaccurate or incomplete citations. This includes references from its Cytator, so you can not only see whether a citation exists, but whether it is good law.

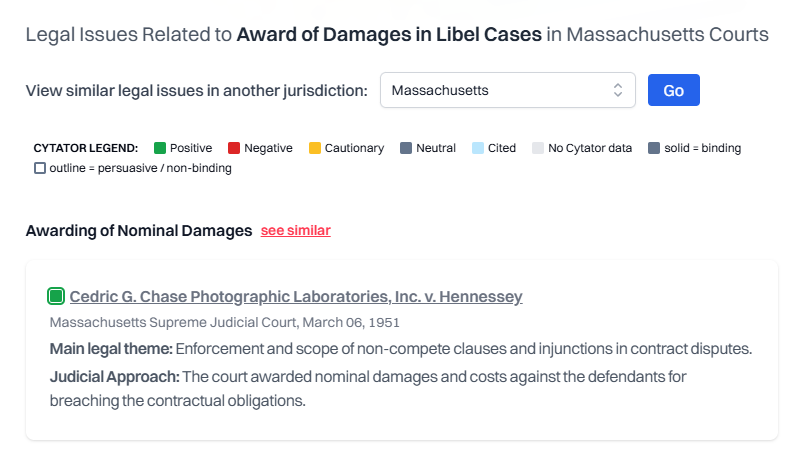

- Legal Issue Explorer. This tool allows you to see how courts approach similar legal issues, even when described in different terms. Use it to spot related issues and compare how they are treated across different jurisdictions.

- Enhanced search. You can now search using natural language queries, keyword search or case name search, including the ability to use Boolean-style operators. Results include the Cytator treatments.

- Case Analysis. Cases now include issue-by-issue insights including holdings versus dicta, procedural posture, circuit splits, precedential value, and more.

They have kept the cost of this upgraded version extremely affordable. Access for non-commercial use is $10 a month. For commercial use (such as by a lawyer), it is just $20 a month.

Citator as Holy Grail

I have written before about development of a robust and reliable citator as the holy grail of legal research platforms. While two products long dominated the market as the gold standard of citators, Shepard’s from LexisNexis and and KeyCite from Westlaw, virtually every other legal research services has sought to build its own citator.

Last year, for example, I wrote about the launch by Paxton AI of its Paxton AI Citator, as well as the launch by vLex of its citator, called Cert. I also recently wrote about Decisis, the legal research platform targeting bar associations, and its simple citator.

Descrybe’s citator promises to do something that these others do not, which is to show not only the subsequent treatment of a case, but also the case’s “backwards” treatment, meaning how it analyzed the cases it cited.

Descrybe gave me advance access a few days ago to test the new citator and the other paid features. I was intrigued, because getting a citator right is not easy. For example, a 2018 study by a law librarian found that both Shepard’s and KeyCite missed or mislabeled about a third of negative citing relationships. The study found that Bloomberg’s BCite performed even worse, missing or mislabeling over tw0-thirds of negative treatments.

Given that, I was intrigued to try Descrybe’s Cytator.

The Cytator

Now when a paid subscriber conducts a search in Descrybe, the cases listed in the results are flagged with colored icons much like you would see with other citators: green for positive, red for negative, yellow for cautionary, black for neutral, and others.

Click on a search result, and you get a collection of tabs across the top that provide various forms of information about the case. (The available tabs seem to vary with the case.) Tabs include:

- Opinion analysis, providing a breakdown of key details about the case, including its facts, disposition, legal theme, issues and holdings, and more.

- Opinion summary.

- The Cytator case treatment, showing binding citing cases and non-binding cited cases.

- The backward citator, showing how the opinion treated each authority it cited.

- The opinion text.

Among legal research companies and legal research professionals, a common issue of discussion is whether human editors are required to ensure the accuracy of a citator or whether AI can achieve comparable (or better) degrees of accuracy.

I cannot claim to have conducted exhaustive testing of the Cytator, but my experience was that it appeared to be generally correct in its identification of subsequent treatments.

Not Perfect

That said, it did not take me long to find instances where it was not correct. As I said above, no citator is perfect, and the examples I found were ones where there was ambiguity in the citation.

For example, in the case Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706, 575 N.E.2d 734 (1991), Descrybe’s backward citator shows that the case expressed caution about an earlier Massachusetts case, King v. Globe Newspaper, 400 Mass. 705, 512 N.R. 2nd 241 (1987). By the same token, the Cytator treatment of King shows a yellow caution flag for the Kourouvacilis case.

In fact, however, Kourouvacilis cited King positively in support of a proposition of law and that should have been reflected with a green flag. But the placement of the citation could have caused confusion for the AI, and possibly even for a human editor. Here is the quote:

“We are in substantial agreement not only with the result reached by the motion judge but also with his reasoning. As we have previously observed, we are not bound to apply the summary judgment standard articulated by the United States Supreme Court in Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, supra. King v. Globe Newspaper Co., 400 Mass. 705, 719 (1987), cert. denied, 485 U.S. 940 & 962 (1988). However, we think it makes eminent good sense to do so.”

The court is citing King in support of the proposition that it is not bound to apply the summary judgment standard of Celotex. It is affirming its statement in the King case that it, as a Massachusetts court, is not bound to follow Celotex.

So, based on my limited testing, it is hard to extrapolate too broadly. But it suggests that there will be instances where ambiguity in the test will lead to incorrect flagging of subsequent (and prior) treatments.

One other issue with the Cytator currently is that I came across a fair number of cases that had no treatments, either of subsequent or backwards citations.

I asked Descrybe about this and they said it is simply a matter of delays in loading all the new data. They said that all the cases should have Cytator treatments within a few weeks.

Brief Checker

Although I did not have extensive time this week to test out all of Descrybe’s new features, I did also try its Brief Checker, which allows you to check the citations in a brief.

Although I did not have extensive time this week to test out all of Descrybe’s new features, I did also try its Brief Checker, which allows you to check the citations in a brief.

As of now, you are not able to upload a brief. Rather, you need to copy the text of the brief and paste it into a window, and then run the checker.

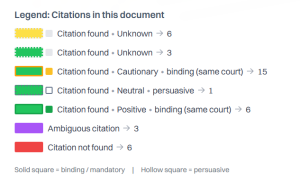

For each case citation it finds, it highlights the citation with a color code indicating whether it found the citation and the status of the citations. (See the legend to the right.)

The checker only looks for case citations. It does not check citations to statutes, regulations, articles, or other sources, and it does not check the accuracy of quotations from cited cases.

It also does not recognize Westlaw citations, and highlights those in red as not found.

But even with these limitations, the tool is useful for its ability to quickly and easily check case citations and protect against hallucinations and other errors.

Bottom Line

With today’s launch of its Legal Research Toolkit, and especially its Cytator tool, Descrybe has taken a major step forward towards becoming a viable legal research service for legal professionals, especially given its low cost of access of only $20 a month for commercial users.

Given that it has only case law and no other primary or secondary legal sources, such as statutes, most lawyers would still need to supplement their research using other tools.

But with another innovative and low-cost legal research service, Casetext, now gone, thanks to its acquisition by Thomson Reuters, there is a need for a service such as Descrybe — and there is a huge opportunity for Descrybe to fill that gap.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog