One impact of the pandemic has been a surge in new business startups, and that has meant a corollary surge in trademark applications. In the first year of the pandemic, trademark applications rose by a third, to 659,000 from the previous all-time high of 495,000 in 2019. So far this year, the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office has received over 400,000 applications and issued nearly 230,000 registrations.

At the same time, trade in fake goods has become a $509-billion-dollar industry, with one estimate saying that roughly one in four U.S. consumers has unknowingly purchased counterfeit items online.

For trademark lawyers, those trends mean that the challenge of protecting their clients’ trademarks is greater than ever. Now, two AI engineers who previously worked together at an autonomous car company have teamed up to help lawyers address that problem.

They have developed advanced AI-driven image recognition technology that can scan both e-commerce sites – such as Amazon, Shopify and Etsy – and USPTO applications to identify and flag visually or textually similar elements that may pose a threat to their clients’ trademarks.

They are now bringing this technology to the market through their company Huski, for lawyers to use both for search and watch – to clear a client’s proposed trademark or watch new applications for a potential conflict – and for brand protection – to monitor for potential brand infringement by products in use in e-commerce.

No other product has ever come to market offering both USPTO image searching and monitoring and e-commerce trademark monitoring for images, Huski’s founders say, although others have evolved to now offer both services through acquisitions.

(I looked at some of the competitors’ websites to better understand exactly what kind of image search they offer, but based on their websites alone, it is difficult to determine that.)

Huski also says it offers these services at a fraction of the cost of its competitors. More on cost below.

(Read more about Huski — and a special discount offer — in the LawNext Legal Technology Directory.)

Powerful Image Recognition

Recently, Chief Executive Officer Henry Du and Chief Technology Officer Guan Wang, the cofounders, and Tessa Molnar, senior manager of sales and business development, gave me a briefing on the company and a demonstration of its product.

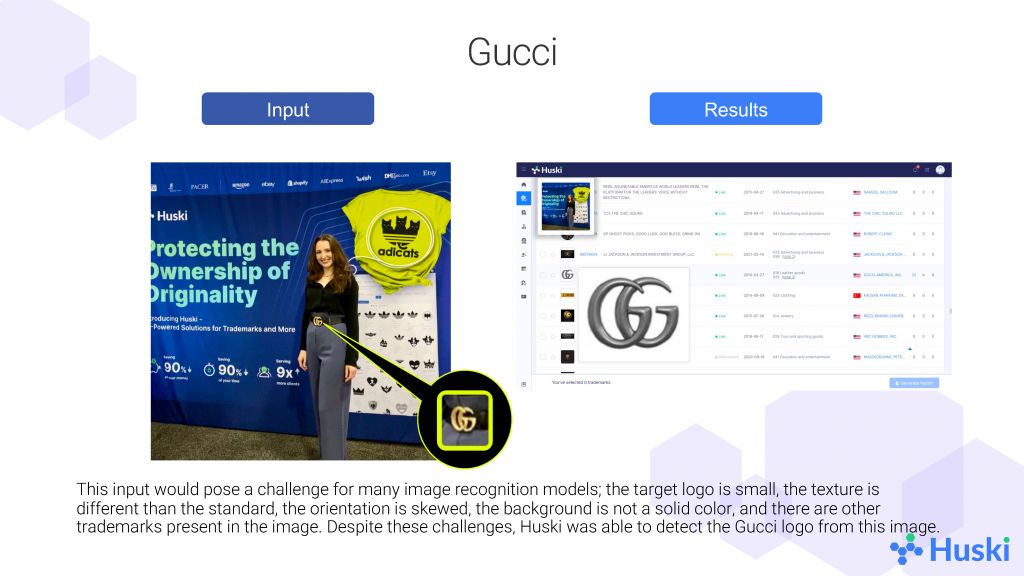

The image-recognition technology appears to be quite powerful. In the image above, Huski is able to detect the Gucci logo on the woman’s belt buckle, even though the logo is small within the image, its orientation is skewed, and the image contains other trademarks.

(That woman, by the way, is Molnar in Huski’s booth at the recent annual meeting of the International Trademark Association, where the company introduced its product.)

This level of image detection is important, Molnar said, because someone who is infringing might not label the image correctly or use a precise copy of the trademark.

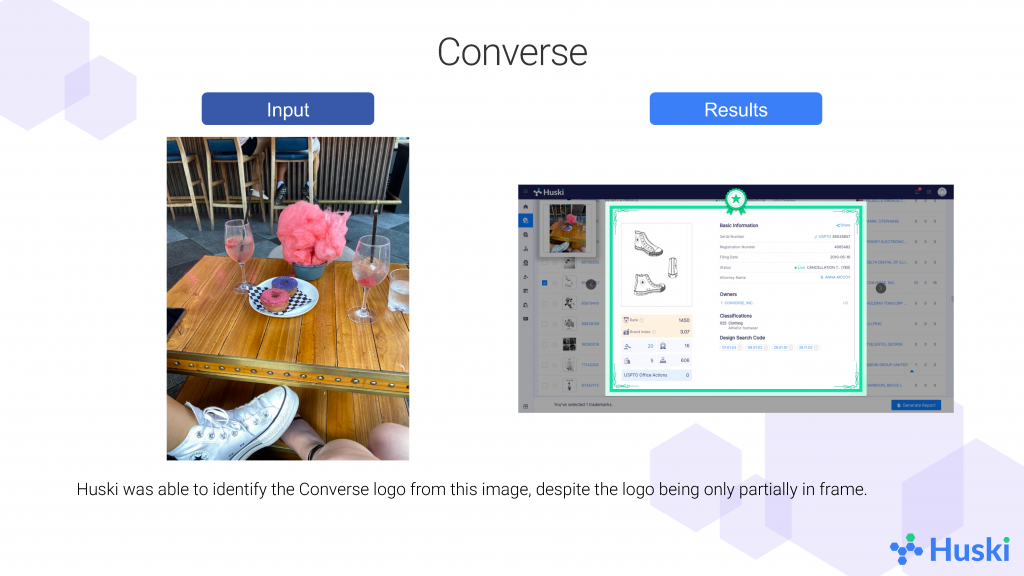

In this example, the technology is able to identify the Converse logo, even though it is only partially shown in the image.

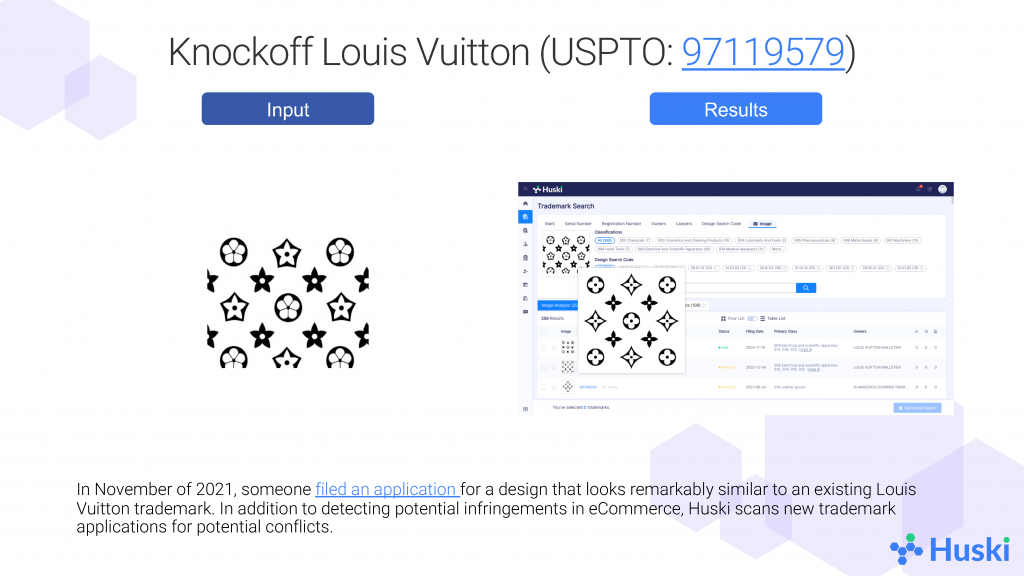

This final example shows Huski’s search of the USTPO database, in an instance where someone filed an application for a design that Huski identified as similar to an existing Louis Vuitton trademark.

Robots Teaching Robots

The cofounders got the idea for the product after hearing a lawyer friend complain about having to turn away business because of the time-consuming process of manual evidence collection for trademark enforcement cases.

“We built Huski to free lawyers from the tedious, time-consuming and low-profit chores of taking listing screenshots and combing through pages upon pages of products when searching for infringing marks online,” said Wang.

They were inspired to tackle the problem by their experience working with autonomous cars, where image recognition technology is used to train cars’ software to navigate common objects on the road, such as a squirrel or a fence.

But they quickly concluded that approach would not work for trademark images, because there are millions of images and not enough data to train the computer sufficiently to recognize each image. Plus, the need to individually train the software for each image would have made the product unaffordable for many law firms.

Instead, they developed a self-taught machine learning model in which separate algorithms work together to teach the other. The model enables the technology to accurately identify millions of trademarks, even from low-quality or distorted images.

“We have robots teaching robots,” Wang said.

He analogized Huski’s software to the evolution of the game-playing AI programs developed by Google’s DeepMind, starting with the original AlphaGo – which had to be trained on thousands of human games – to AlphaGo Zero – which was trained only on the basic rules of the game, without examples – and then to AlphaZero – which was given no training of any kind and mastered three different games in three days.

Similarly, Huski’s software is not trained using rules for what makes images similar or not. Rather, it is told that certain images are similar, and the software figures out for itself why, getting better and better over time.

Searching and Monitoring

Based on the demonstration I saw, the software is also fast and easy to use. An image search of the USPTO’s TESS database (Trademark Electronic Search System) required only loading the image and hitting search, and results appeared within seconds, showing the visually similar images that the software detected.

This type of search cannot be done directly through the USPTO’s website, as TESS does not allow image searching, directly, but requires the use of design codes to search images.

Huski can also perform text searches, and can search both phonetically for similar matches and exactly for precise matches.

Huski’s e-commerce monitoring is not search based, but ongoing, and currently covers more than 60 million listings, soon to reach 100 million listings. It includes coverage of virtually all major e-commerce sites, including all of Shopify, as opposed to just individual shops that operate on the Shopify platform.

While there are other tools available to attorneys to search and monitor the USPTO database, and still other brand-protection tools for monitoring for infringements, Huski is unique in bridging the gap between the two types of image data.

Subscription Pricing

It also does this at lower cost. While most trademark search tools charge by the search, at prices from $100 to $800 per search, Huski allows unlimited text and image clearance searches for $299 per month.

(You can save even more on that with a discount the company offers through its listing in the LawNext Legal Technology Directory.)

It charges additional amounts to monitor new USPTO applications for trademarks that may conflict with a client’s existing trademark registration, with the option to also monitor e-commerce for potential infringements.

The pricing for e-commerce monitoring is determined by the customer, since different brands will have different numbers of trademarks and different numbers of potentially infringing images.

Although I have not verified these prices, Huski says that other USPTO design search products charge substatially more: Clarivate charges $745 to $6,580 for a single search, Corsearch charges $840 to $5,065 for a single search, and Markify charges $109 for a single search.

Getting started on the cloud-based platform is quick and easy. When an attorney first registers, they see a Trademark Lifecycle Management dashboard. Huski pulls all the data from the USPTO trademark register where that user is the attorney of record.

Once that is loaded, the attorney can see all clients’ trademarks and actions, and also see a profile of the lawyer showing data on numbers of clients, trademarks, office actions, and the like.

While Huski is currently focusing on trademarks, it believes that its proprietary technology can eventually be leveraged to protect other types of IP, such as industrial designs and copyrighted materials, as well as emerging Web 3.0 assets such as NFTs.

“As innovators ourselves, we believe that creativity and innovation are what drive us forward, and we want all individuals, professionals, and businesses of all sizes enjoy and benefit from the process of innovation,” said CEO Du.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog