For startup companies that go through high-profile incubator programs or whose founders come from prestigious schools, the traditional word-of-mouth referral network works just fine for finding a lawyer to represent them.

But for many other startups, it can be difficult to find a lawyer they know they can trust and who is a good fit for their needs. It is often even more difficult for founders of color and founders who are women.

A company launched earlier this year called Anü aims to tackle that problem by using artificial intelligence to match startups with the lawyer best suited to represent them.

It also aims to enhance diversity on both sides of the equation — helping diverse founders get the right legal help and encouraging diversity among law firms hired by startups.

The starting point by which it does this is through a different approach to client intake. Rather than require the startup to complete a form questionnaire with a long list of drop-down boxes, Anü asks it to write a narrative description of its business and its legal needs.

Anü then uses neurolinguistic modeling to analyze and score the narrative for certain factors. Based on that scoring, Anü passes the startup on to the appropriate law firm.

Started As School Project

The company was founded by a lawyer and data scientist who met while pursuing advanced degrees at Cornell University. Tiyani Majoko was a lawyer in South Africa who moved to the United States to get an LL.M. in law, technology and entrepreneurship. Maxwell Wulff earned a master’s degree in engineering with a focus on operations research and information engineering.

The seeds of Anü were sown when the two collaborated on a school project to build a risk-management tool to help startups evaluate the risk they carried. That work led them to consider the role of professional networks in relation to risk, and to the conclusion that the better the quality of a company’s network, the better its access to resources such as legal help.

Traditional professional referral networks enable both the client and the lawyer to enter into the relationship with a greater degree of confidence, Majoko told me during a recent conversation. They provide the client assurance that they can trust the lawyer and the quality of the lawyer’s work. For the lawyer, they provide assurance that the client is serious about its business and has the ability to pay.

Anü is an attempt to disrupt that traditional referral network, she said, or at least to extend the benefits of such networks to those who might not otherwise have access.

Nuanced Descriptions

Anü’s intake process seeks to avoid long lists of drop-down boxes and put it on the client to talk about itself, Wulff told me.

“We put a lot of emphasis on the clients to write about themselves,” he said. “We want to get a more nuanced description from the founder.”

“The more someone writes, the more serious they are about their legal matters,” he said. “Someone who is truly serious will be somebody who’ll write more and have a detailed description.”

Wulff said that Anü’s neurolinguistic model scores these narratives to determine how excited the founder is about the company, how committed the founder is, and the founder’s expertise in the domain in which it is operating.

“We are making sure that our legal professionals are matched only with people who are serious about their idea,” Wulff said. “We can’t guarantee conversion, but we can guarantee that these are founders who at least one of our lawyers will be excited to talk to.”

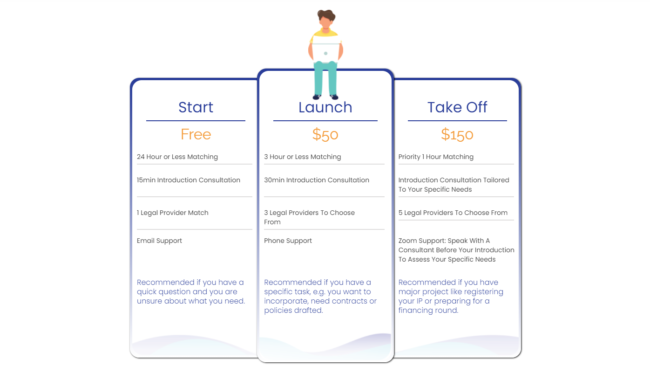

Another factor by which Anü evaluates startups is willingness to pay for legal services. The company offers three tiers of pricing, with the first tier free. Whether a client choose the free or a paid option is factored into the evaluation of how serious the client is about the startup.

Informed Matches to Lawyers

If a startup passes Anü’s vetting, then, based on the neurolinguistic modeling, it makes an “informed match” to an attorney, taking into account the startup’s industry, legal needs and jurisdiction.

After the match is made, the client gets an email providing information on the match and link to a scheduling page to set up an appointment with the lawyer. The lawyer learns of the match only when the client schedules the meeting.

Founded just six months ago, Anü has so far partnered with just seven law firms, and those firms cover 11 states (although some of the work, such as IP, is not state-specific).

Majoko and Wulff told me that they prefer to work with firms at this point, rather than individual lawyers, because they do not have the resources to vet individual attorneys.

Of the firms with which they partner, they ask that they be available to work with founders remotely, give the startups their full attention, provide customized and flexible pricing, and be involved in their local startup ecosystem, such as, for example, by donating office hours at local incubators.

Majoko and Wulff also seek diversity in the firms with which they partner. Of their current roster of firms, 30% are Black owned and 100% have women partners.

So far, firms have paid nothing to be part of this service. Starting in December, the company will begin to charge firms a monthly marketing fee to be included.

Future Development

Majoko and Wulff founded their company last May and are currently engaged in early-stage fundraising in order to build out Anü’s functionality and market.

Their plan is to build up the functionality of the platform, so that attorneys can use it for scheduling, document storage and payments.

They are also working on building a “recommendation engine” for clients that will use Anü’s modeling to help startups better understand the types of legal issues they should address. It might tell a founder, for example, that other startups in the same industry typically have these types of contracts in place, and then help the founder find help to develop those contracts.

Longer term, they hope to expand into other types of clients and practice areas, and even into other vertical professional markets.

“We want to be a resource for companies to find all professional services they require across all verticals,” Majoko said. Besides legal services, they hope to add accounting, marketing, copyrighting and other business-to-business services.

Bottom Line

Law firms like to brag in their marketing that they understand their clients’ businesses. Anü’s concept is to use AI to better understand a startup’s business before matching it with a lawyer.

It is a promising and intriguing idea that should ultimately benefit both clients and firms. Whether it works, I cannot say, but Majoko and Wulff say the clients and firms they’ve worked with so far have been enthusiastic about the results. In six months, they have helped 40 startups get access to legal services.

They also deserve credit for their commitment to driving diversity among the law firms with which they work. Although they have so far partnered with fewer than a dozen firms, 30% are Black owned and all have women partners.

The one aspect of their business plan on which I’d urge caution is to become a broader B2B marketplace for businesses, connecting clients not just to lawyers, but also accountants and marketers and others.

This is exactly what Atrium tried to do in its final days, morphing from legal services company to a professional services marketplace dedicated to startup founders.

Indeed, when I mentioned this, Majoko’s response was, “We are haunted by the ghost of Atrium.”

They need not be. They have a promising concept in what they’ve already created. I hope that, for the time being, they focus on building that up and on providing a better way to match potential clients with the right lawyers for their needs.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog