Fewer than four months after the University of Chicago Law School announced it would be launching an AI Lab, a course designed to teach law students how to build generative AI tools to help people who cannot afford an attorney, the 10 students in the lab’s inaugural class have developed and launched their first product.

Called LeaseChat, it is a free AI tool designed to help renters across the United States analyze their leases and understand their legal rights. With more than 40 million rented properties nationwide, the tool aims to level the playing field for tenants navigating complex lease agreements and landlord-tenant law.

LeaseChat provides four core features, all designed to help renters understand both the law and their specific lease terms:

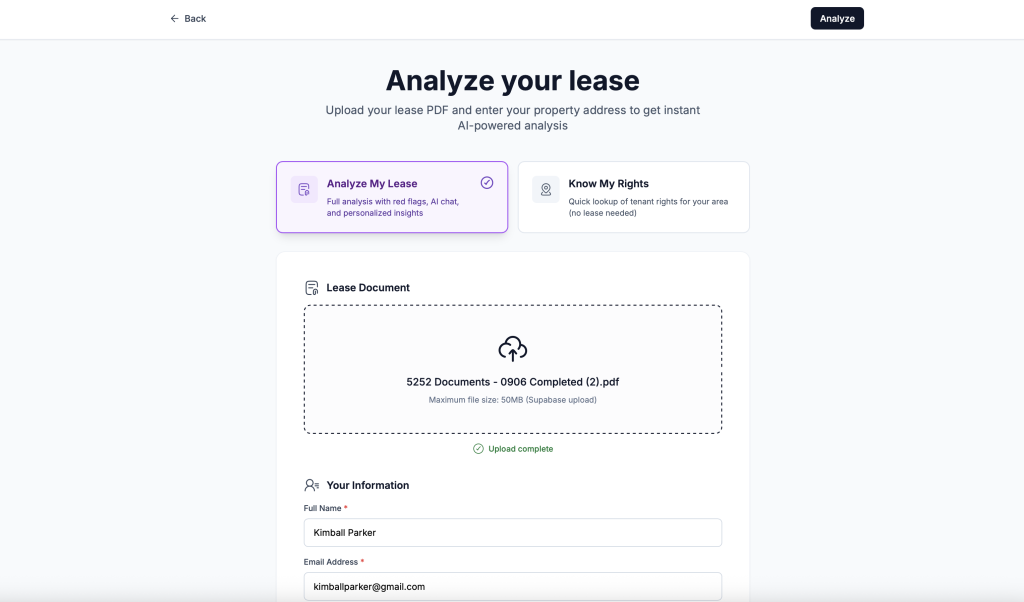

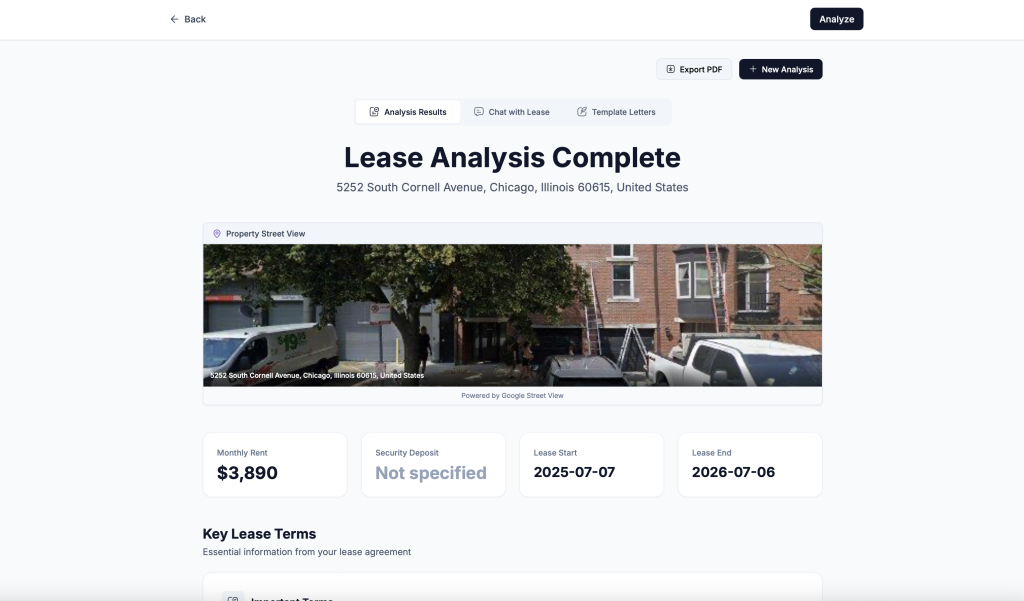

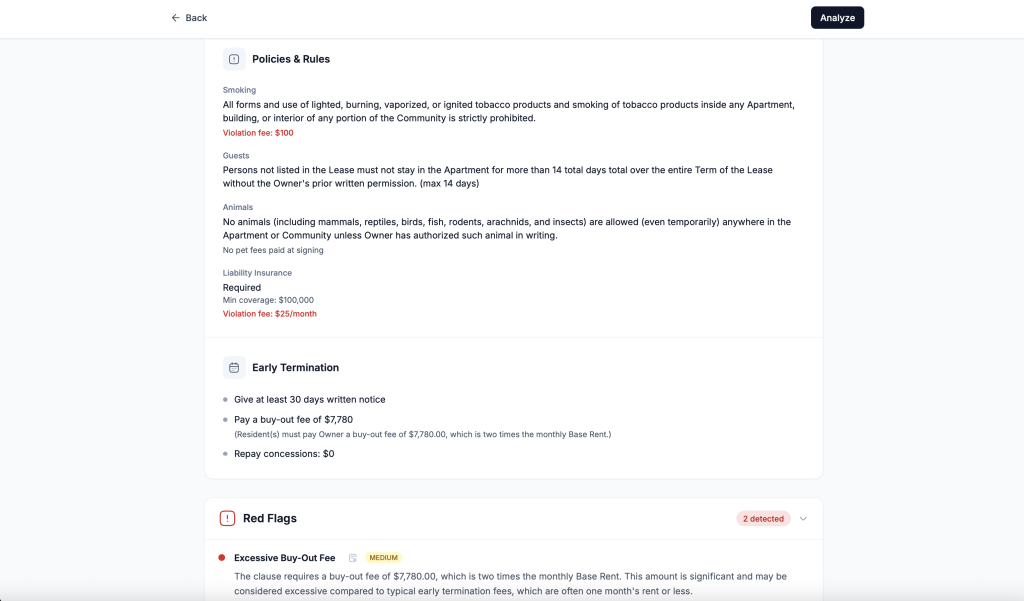

- Lease Analyzer: Renters can upload their lease and receive an AI-powered analysis that identifies any red flags. For example, the system will flag unusually high security deposits or problematic clauses.

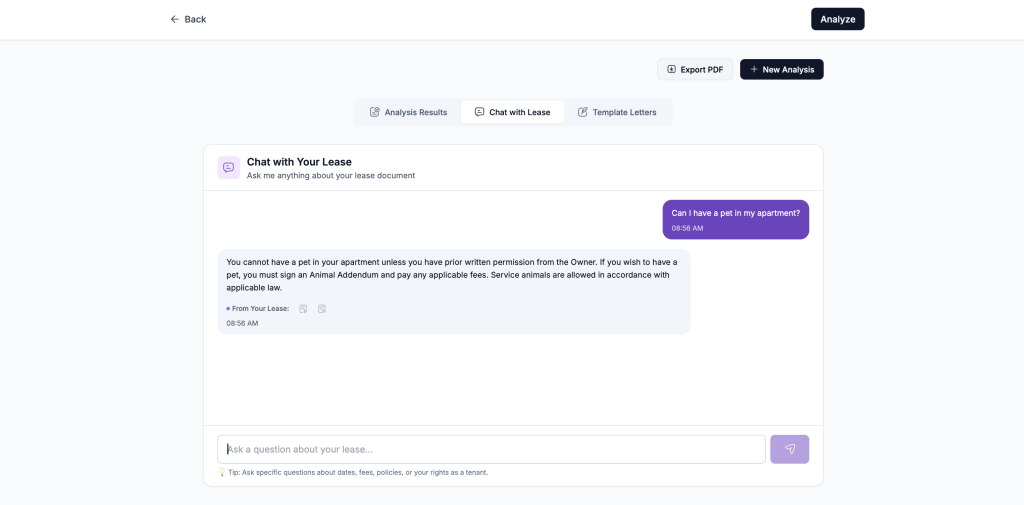

- Lease Chat: Users can ask questions about their lease in plain language and receive answers with direct citations to specific lease provisions, complete with page references.

- Legal Rights: Based on the lease location, the tool outlines applicable laws and tenant rights for that specific city and state, covering everything from repair timelines to notice requirements for landlord entry to rules around returns of security deposits.

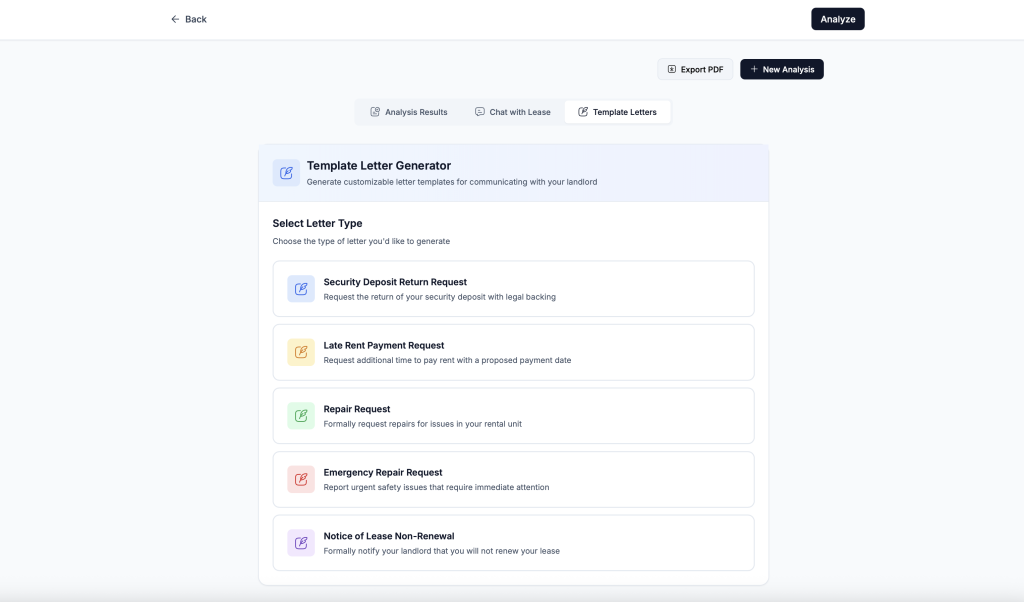

- Letter Drafter: The platform can help renters draft correspondence to landlords about repairs, late rent, deposit returns and other common issues.

All of LeaseChat’s features are also available in Spanish, via a toggle button at the top of the site’s homepage.

“It’s difficult for renters to know their legal rights because they need to understand both the law and their lease,” said Kimball Dean Parker, the head of the AI Lab. “LeaseChat helps with both. Our hope is that this tool can level the playing field and help millions of renters to know and exercise their rights.”

Built Entirely By Students

Two aspects of LeaseChat’s development are particularly remarkable.

For one, it was built entirely by law students. They built the tool from scratch, researching the law, coding the platform, designing the user experience, and conducting the outreach.

For another, it was built extremely quickly. In fact, the students had built the initial prototype within just days of starting the class. By Oct. 15, I was able to see a functional demonstration of the tool, presented to me by Parker and Adan Ordonez, a second-year law student who participated in the lab and led the coding effort.

In fact, Ordonez exemplifies how a new generation of law students can contribute as builders of legal tech. Despite having no formal computer science training — he majored in psychology and spent time as a professional baseball player and coach with the Philadelphia Phillies — Ordonez taught himself to code while working with the Phillies’ data-analytics group.

Using Cursor, an AI-powered coding platform, Ordonez was able to build the first working prototype over a single weekend, spending just five to six hours on it. “We had our first class two Fridays ago and I think that Sunday we had the first prototype,” he told me during the Oct. 15 demonstration.

Bridging Domain Knowledge and Tech Skills

The speed of development and ability to employ AI reflect a broader transformation in how legal technology can be built, Parker said. He noted that what now takes days used to require months of work with a full engineering team. “AI has made coding so much more accessible. That barrier is so much thinner now.”

Ordonez emphasized how AI tools are eliminating the traditional friction between legal expertise and engineering talent. The AI Lab, for example, included an LLM student who is a former BigLaw partner. “He doesn’t know how to program, but he knows way more than I would about the law.” The friction, he said, would be in communicating that legal expertise to the engineers.

But modern AI coding tools are changing that dynamic, he said. “With these tools now, you can give people that have the domain knowledge the tools to build at least a prototype and then just hand it off to the engineers and say, ‘Hey, make this work.’ Or if you’re a little technical, and you really want to study up, you could just create it all yourself. I think that’s incredible.”

In fact, the make-up of the AI Lab reflected the range of relevant skills students bring to law school from their pre-law careers, Parker said.. In addition to Ordonez with his coding skills and the former BigLaw partner with his legal expertise, the class includes a former public relations professional at Google and a marketing professional with expertise in search engine optimization.

How LeaseChat Works

When a user uploads a lease to LeaseChat, the system converts the PDF into HTML format to enable AI analysis. The platform then runs a series of queries to analyze the lease terms and identify the jurisdiction to determine applicable laws.

The analysis identifies key information such as rent amount, security deposit and lease dates, then flags potential problems. For instance, in a test demonstration, the system identified a security deposit equal to two months’ rent as unusually high and potentially problematic.

The tool also provides street view images of the rental property, plain-English explanations of legal jargon, and highlights key dates like move-in dates. Users can export the entire analysis as a PDF to save, share with an attorney or keep for future reference.

To provide location-specific legal information, LeaseChat relies on ChatGPT. Originally, the class planned to build a proprietary database of landlord-tenant laws, but as the semester went on, that changed.

Parker explained to me that the students actually started to build that database, assuming that if they layered AI over that information it would produce more accurate results than the base AI models. But as they used ChatGPT 5 and other “reasoning models,” they found that there was no accuracy gain.

They consulted with James Evans, a data science professor at the University of Chicago, who has been studying how “reasoning” models work. After he advised them that there may not be any accuracy gain from using a database of legal summaries, the class pivoted.

They set up a layered prompting system, Parker said, and worked on (1) assessing and grading the answers and (2) refining the prompts to generate the answers we wanted.

“This process has taken months and we’re at a place now where we feel great about the responses,” Parker said. “It can outline the law in any city/state/county in the nation.”

A New Model for Legal Education

As head of the AI Lab, Parker brings significant experience. In 2017, while still a practicing lawyer, he founded and ran the LawX lab at Brigham Young University Law School, which pioneered the model of having law students build legal technology tools to expand access to justice.

That inaugural BYU lab developed Solo (originally called SoloSuit), a product to help consumers navigate debt disputes, which spun off into a successful private company led by George Simons, who was one of the BYU students who developed it.

The LawX experience led Parker to team up with the technology law firm Wilson Sonsini Goodrich and Rosati to launch SixFifty, a legal technology company that automated employment law compliance.

Earlier this year, this blog exclusively reported that SixFifty had been acquired by the payroll and human resources company PayChex.

In bringing the expertise he began to develop in 2017 with LawX to the University of Chicago, Parker said that the difference between then and now is striking.

Where LawX students would labor for months with engineering teams before releasing anything, the AI Lab can iterate through multiple versions of a product in a single academic term. At LawX, he said, “we wouldn’t release anything until maybe a month after the term. And that was because we were laboring with the engineers.”

Now, the AI Lab was able to release its initial version just weeks into the term.

“Before, you would draw it out on a piece of paper … and then you’d ask someone to use their imagination,” he said. You would show them the drawing and ask if they would use an app such as that. Now, you can go right to developing the app and get user feedback almost immediately.

The Perfect Place

Parker, who teaches the class while commuting weekly to Chicago from his home base in Utah, plans to run the lab annually. The University of Chicago operates on a quarter system, so the class began just three weeks before the launch and will conclude in late December.

“The University of Chicago is just the perfect place for this,” Parker said. “Such smart students coming in with such interesting skill sets.”

For Nanako Watanabe, a law student participating in the AI Lab, the experience has been transformative: “The AI Lab has helped open my eyes to what the latest technology can do and what it’s like to build an AI product for a population that needs help. It’s one of the most meaningful experiences I’ve had in law school.”

Adam Chilton, the law school’s dean, said, “The AI Lab provides a unique learning experience for our students to build and launch an AI product. It also produces a tremendous public benefit that can help millions of people across the nation.”

As Parker observed about students like Ordonez: “Someone like Adan is going to be able to be such a powerful legal technology entrepreneur. With this skill set to get ideas out … the hardest thing to do is to validate an idea and to find demand. Being able to string something up, test it, see if there’s any demand, pivot, adjust, and find where that line of demand is — you can move so fast now.”

The bottom line of the AI Lab and its LeaseChat project may be that the future of legal technology innovation may increasingly come from law students and lawyers themselves, empowered by AI coding tools to turn their domain expertise into functional products without waiting for traditional engineering teams.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog