Five years after Arizona and Utah launched groundbreaking reforms to liberalize legal services regulation, a new comprehensive study from Stanford Law School’s Deborah L. Rhode Center on the Legal Profession reveals both the promise and the complexities of regulatory innovation in the legal sector.

The report, Legal Innovation After Reform: Five Years of Data on Regulatory Change, is an update to a report the Rhode Center published in 2022, which offered the first real evidence-based analysis of the Arizona and Utah programs. In an episode of my LawNext podcast that year, I discussed the report with its authors, David Freeman Engstrom, co-director of the Rhode Center, and Lucy Ricca, executive director of the Rhode Center. In this latest update, they are joined as authors by Natalie A. Knowlton, associate director for legal innovation at the Rhode Center.

While this five-year report extends many of the positive findings of the earlier report – such as that liberalization has spurred innovation and benefitted consumers and small businesses – it also finds a concerning divergence between the two programs, with Arizona experiencing explosive growth while Utah has undergone substantial contraction, in part due to political pressures.

Backdrop: A Crisis in A2J

To understand the significance of the Arizona and Utah reforms, it is important to consider the magnitude of the access-to-justice crisis that prompted them. The traditional legal services market has long operated under two fundamental restrictions: unauthorized practice of law (UPL) rules that limit who can provide legal services, and Model Rule 5.4, which restricts who can own law firms and share legal fees.

These regulations have effectively created what many – including the Stanford researchers – describe as a “lawyers’ monopoly” that has stymied innovation and left millions of Americans without meaningful legal help.

It is a stark picture. According to the report, millions of Americans each year face legal challenges with potentially serious consequences – foreclosure, eviction, family disputes, debt collection, workplace discrimination – yet most never seek help from a lawyer or formal legal authority. In high-volume litigation areas like eviction and debt collection, roughly 75% of cases involve at least one unrepresented party.

“Millions of Americans each year cannot get meaningful help with legal issues impacting their lives,” the report says. “Priced out of the market for lawyers and left to navigate a complex and even Byzantine legal system alone, they often face harmful and even devastating consequences for themselves, their families, and their communities.”

Same Problem, Different Approaches

In 2020, Arizona and Utah each launched pioneering but distinct approaches to address these challenges. Arizona chose an “ABS-only” approach, eliminating Rule 5.4’s restrictions on nonlawyer ownership and fee-sharing while maintaining traditional unauthorized practice of law limitations. This allowed the creation of Alternative Business Structures (ABSs) – law firms that can be owned by nonlawyers and funded by external capital.

Utah took a more expansive “ABS+UPL” approach through its regulatory sandbox program. This allowed entities to seek waivers from both ownership restrictions and unauthorized practice of law rules, potentially enabling nonlawyers and even software to provide legal services under appropriate oversight.

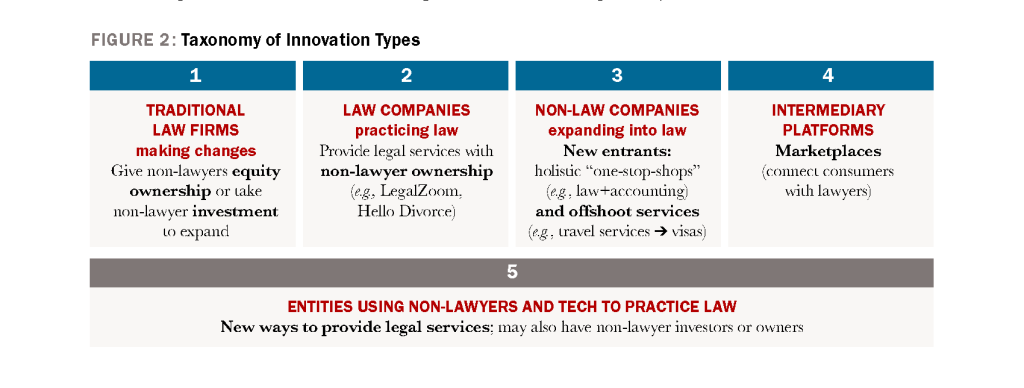

To understand the types of innovation emerging from these reforms, the Stanford researchers developed their own taxonomy. They identified five categories: traditional law firms adapting their structure, law companies (like LegalZoom) entering the market, non-law companies expanding into legal services, intermediary platforms connecting clients with lawyers, and entities using nonlawyers and technology to practice law.

Divergent Trajectories

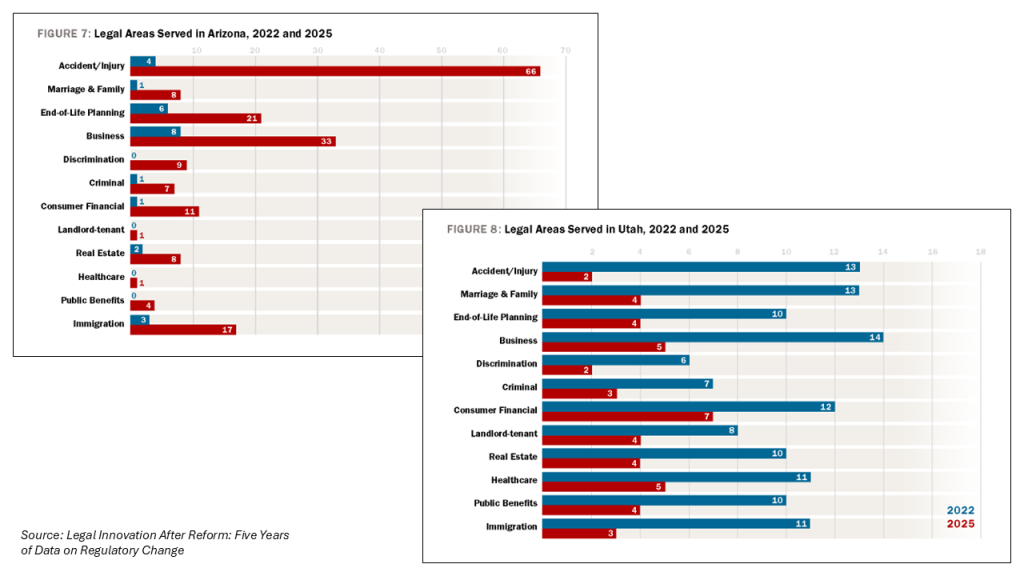

Perhaps the most striking finding of the five-year study is how dramatically the two states’ programs have diverged. Arizona has experienced explosive growth, expanding from 19 authorized entities in 2022 to 136 as of April 2025 – a more than six-fold increase. Utah, conversely, has undergone substantial contraction, shrinking from 39 entities in 2022 to just 11 by April 2025, representing a 72% decrease.

This divergence reflects different regulatory philosophies and political pressures. Arizona’s Supreme Court has largely stayed the course despite facing criticism from business interests and the organized bar. Utah’s Supreme Court, however, has substantially narrowed its sandbox program, citing various concerns and implementing what it calls “Phase 2” requirements that emphasize serving underserved Utah consumers and require more substantial innovation.

The Utah court’s decision particularly impacted ABS-only entities – those seeking only ownership reform without unauthorized practice of law waivers. Many such entities were terminated from the sandbox, though some received partial Rule 5.4 waivers allowing them to continue operating under modified arrangements.

Law Firms Adapting

The study finds that there are somewhat distinct patterns in the types of legal innovation emerging from these reforms. In Arizona, traditional law firms adapting their structures represent the largest category – 64% of authorized entities. In many cases, these firms have added nonlawyer owners, accessed new sources of capital, or introduced new service models while maintaining familiar organizational structures.

A particularly noteworthy development, the report finds, is the emergence of “one-stop shops” – entities that combine legal services with other professional services. These entities can address multiple client needs simultaneously. Examples include accounting firms adding legal services, companies offering both immigration and travel services, or firms providing comprehensive end-of-life planning that includes both legal and financial components.

The law company category includes well-known entities such as LegalZoom and newer entrants such as Rocket Lawyer Attorney Services, which supplement document generation with direct legal services. Arizona hosts 21 such entities, representing approximately one-sixth of the state’s total entities.

The Role of Technology

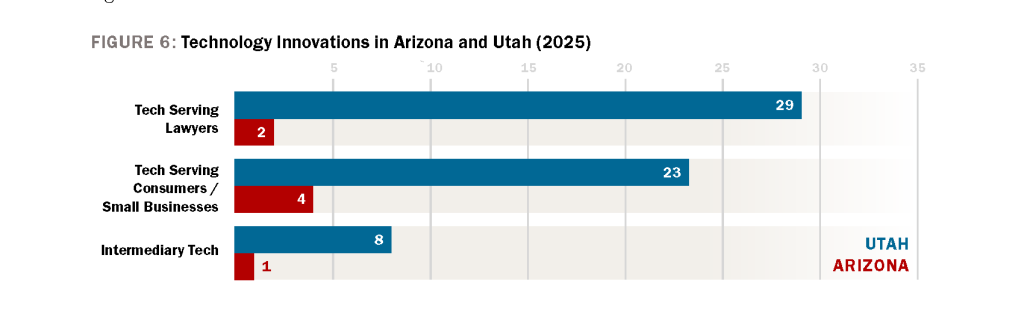

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study concerns technology adoption, particularly given that an explicit goal of Utah’s program had been to encourage legal technology innovation. Despite the regulatory sandbox’s theoretical potential for AI-powered legal services, the reality has been more modest, the report finds. Currently, no entities in Utah’s sandbox operate using high-innovation software models without lawyer oversight.

The researchers identify several possible explanations for this technological gap. Technology development requires substantial resources and expertise, and Utah’s relatively small legal market may not justify such investments. Additionally, the sandbox’s experimental nature and repeated pivots may have created too much uncertainty to attract the capital necessary for innovative technology development.

This technology adoption challenge is not limited to Utah. Even in Arizona, most entities are not deploying cutting-edge legal technology. The study suggests this reflects broader barriers that have constrained legal tech generally, including challenging market economics for serving cost-conscious consumers and fragmented court technology systems.

Serving Individual Consumers

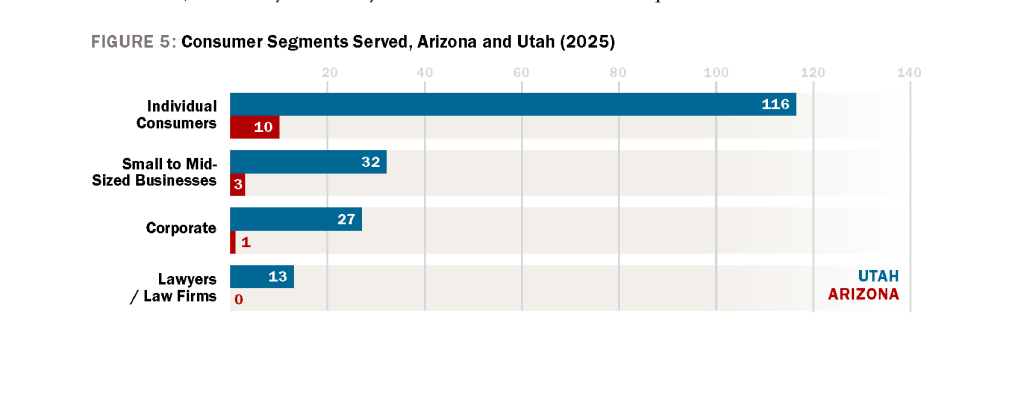

A consistent and encouraging finding across both states is that individual consumers remain the primary beneficiaries of these regulatory innovations. In Arizona, 116 of 136 entities (85%) reported plans to serve individual consumers, while 10 of 11 remaining Utah entities (91%) indicated the same focus. This represents a clear success in achieving reformers’ goal of expanding access to legal services for ordinary people rather than just corporate interests.

The study also reveals important nuances in how different regulatory approaches serve various populations. Utah’s sandbox, with its authorization for nonlawyer service providers, appears particularly effective at reaching low-income populations. Four Utah entities specifically target free legal services to low-income individuals, highlighting the potential importance of UPL reform in spurring innovation for underserved communities.

Technology innovations in both states focus primarily on serving individual consumers and small businesses rather than large corporations, suggesting these reforms are successfully democratizing access to legal innovation.

Little Evidence of Consumer Harm

A critical question for any regulatory reform concerns consumer protection. The study finds remarkably little evidence of consumer harm in either state. Utah’s data through April 2025 shows only 20 consumer complaints across all sandbox entities, yielding a harm-to-service ratio of approximately 1:5,869 based on reported legal services delivered.

In Arizona, two ABS entities and their compliance lawyers faced formal disciplinary action. However, these cases involved procedural and oversight issues rather than systematic consumer harm, the report says, and both orders noted the entities’ cooperative attitudes and corrective measures.

This low rate of consumer harm is particularly significant given the frequent concerns raised about nonlawyer ownership and innovative service delivery models potentially compromising legal quality or professional standards.

The Continuing Role of Lawyers

Despite concerns that regulatory reform might sideline attorneys, the study finds that lawyers continue to play central roles in authorized entities across both states.

In Arizona, 134 of 136 entities employ lawyers to provide legal services directly, while even in Utah’s more permissive sandbox, seven of 11 entities have lawyers providing legal services and 10 entities deploy lawyers in management or compliance roles.

This finding counters critics’ concerns that deregulation could lead to the “corporate practice of law” and undermine professional independence and ethical obligations. To the contrary, the data suggests that regulatory reform has enabled new business models while preserving lawyers’ essential expertise and ethical training.

Emerging Challenges

The study also examines three emerging issues that have generated significant attention and controversy. The first concerns private equity and litigation funder involvement in Arizona ABSs. Through detailed analysis of ownership structures, the researchers identified 17 entities with clear ownership by litigation finance companies, venture capital firms or private equity firms – representing about 12.5% of Arizona entities.

While this is notable, the study suggests the actual extent of such involvement may be less dramatic than some critics have claimed. Importantly, half of Arizona’s ABS entities appear to have no direct or indirect involvement by litigation funders or private equity firms, though the researchers acknowledge this may change over time as entities seek additional investment after initial authorization.

The second emerging issue involves the concentration of entities in personal injury and mass tort practice areas. Approximately half of Arizona ABSs (75 entities) proposed to practice at least partially in personal injury and contingency fee case types, with 14 of the 17 entities with private equity or litigation funder ownership operating in these areas.

This concentration has raised concerns about Arizona becoming a “mass torts capital” that primarily benefits out-of-state litigation rather than local access to justice.

As a U.S. Chamber of Commerce comment quoted in the story put it: “Arizona should not allow hedge funds, litigation funders, and others to set up volume-focused, for-profit claims mills, advertising and collecting claims for out-of-state plaintiffs. There is no benefit to Arizona and its citizens in unintentionally making itself the mass torts capital of the United States.”

The third issue concerns the limited deployment of generative AI despite its potential to transform legal services delivery. Few entities in either state are leveraging advanced AI technologies, the report finds, despite Utah’s regulatory framework being specifically designed to accommodate such innovation.

Political Pressures

A key difference between this five-year study and the previous two-year study is the extent to which political pressures have shaped the trajectory of these reforms.

Arizona has faced substantial criticism from business interests and chambers of commerce, leading the Arizona Supreme Court to form a Task Force on Alternative Business Structures to examine third-party litigation funding and other concerns. But even in the face of such challenges, the Supreme Court has maintained its commitment to the reform program, the report says.

In Utah, political opposition had a more dramatic impact on reshaping its regulatory initiatives. Legislative pressure, criticism from the plaintiffs’ bar, and concerns about entities operating outside Utah with limited local presence contributed to the court’s decision to substantially narrow the sandbox program.

These political dynamics, the report suggests, offer a critical reminder for other states considering similar reforms, which is that regulatory innovation occurs within complex political ecosystems that can significantly influence implementation and sustainability.

Implications for Other States

The study’s findings have important implications for the growing number of states considering regulatory reform. Currently, multiple states are pursuing various approaches, from entity-focused reforms similar to Arizona and Utah to role-focused reforms that create new categories of licensed legal service providers.

Washington State has approved a sandbox program modeled on Utah’s approach, with particular emphasis on legal technology innovation. Indiana and Minnesota are in preliminary stages of considering regulatory sandboxes. Meanwhile, other states like Colorado, Oregon, and New Hampshire have focused on licensing paraprofessionals—nonlawyer legal service providers analogous to nurse practitioners in medicine.

The diversity of approaches reflects different theories about how best to expand access to legal services while maintaining appropriate consumer protections. Some states are pursuing multiple reform strategies simultaneously, potentially providing various pathways for legal innovation.

Looking Forward

The study concludes that regulatory reform sits at a crucial crossroads. While Arizona and Utah have demonstrated that entity-focused reforms can spur beneficial legal innovation and expand access to justice, they have also raised important questions about political sustainability, scalability, and the appropriate balance between innovation and regulation.

The researchers note that future analyses will need to explore the intersections between different reform approaches. Questions remain about whether sandbox models like Utah’s initial approach are most effective, whether decoupled reforms like Arizona’s prove more sustainable, or whether role-focused reforms might offer better returns on limited political capital.

Needless to say, the rise of gen AI adds another layer of complexity, with some states like Minnesota specifically considering AI-focused sandbox programs to address both the promise and the risks of artificial intelligence in legal services delivery.

The bottom line is that this study represents the most comprehensive empirical analysis to date of legal regulatory reform, providing critical data for policymakers, legal professionals and technology innovators seeking to understand how regulatory changes can expand access to justice.

As more states consider their own reform initiatives, the experiences of Arizona and Utah offer both encouragement and important cautionary lessons about the complexities of professional regulatory change.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog