The jury of popular opinion is divided on the writing style of the newest justice on the Supreme Court. Slate pronounced Neil M. Gorsuch a terrible writer. But a forthcoming quantitative study of his published opinions concludes that he “does exceedingly well according to the standards of good writing that legal writing authorities espouse.” His writing is the subject of a mocking Twitter hashtag and has been covered in the New York Times.

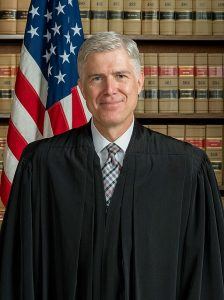

Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch; photograph by Franz Jantzen, 2017.

But what do legal editing programs think of Gorsuch’s writing? There are several such programs available to lawyers. The most-popular ones operate as add-ins to Microsoft Word, performing grammatical and stylistic analyses of briefs, memoranda and other legal documents.

I decided to test Gorsuch’s opinions against three of these programs: BriefCatch, PerfectIt and WordRake. I had never before used BriefCatch. I had previously reviewed both of the other programs, calling PerfectIt a virtual, eagle-eyed proofreader, and twice testing WordRake against Supreme Court opinions, first against the writings of Justices Antonin Scalia and Elena Kagan, and then against Justices John G. Roberts Jr., Clarence Thomas and Stephen G. Breyer.

At the outset, it is important to note that these three programs operate differently and perform different functions. WordRake and BriefCatch are similar to each other in that they focus on enhancing clarity and concision. In contrast, PerfectIt is a proofreading tool; its suggestions are more granular and encompass punctuation, formatting, citation style, capitalization, and more. WordRake and BriefCatch perform a one-time analysis — one calls it a “rake,” the other a “catch” — while PerfectIt performs a series of tests.

Texas v. New Mexico

I started with Gorsuch’s majority opinion in the water dispute, Texas v. New Mexico. This was the opinion in which Gorsuch “seemed to hit his stride” as a writer, Nina Varsava, author of the study of his opinions and both a Yale law student and Stanford doctoral candidate, said in the New York Times.

When I ran the three editing programs against this opinion, PerfectIt immediately caught something neither of the others did. One of its first tests looks for spelling variations, and it found the same word spelled two different ways, “mold” and “mould.” In this case, the variations were intentional. Gorsuch quoted an opinion that used “mould,” but in his own use of the word, he chose “mold.”

Another PerfectIt test, this one for capitalization, also caught something neither of the others did. It noted that the word “Compact” appeared in the opinion 24 times capitalized and four times not capitalized. It gave me the option of using one form or the other in all instances (or of leaving them as they were), but also warned to check the context, as words may need capitals in one place but not another. Here, the differences in capitalization were intended. Some referred to a specific compact by its formal name and thus were capitalized, while others referred the noun in its generic sense. PerfectIt also caught inconsistent capitalization of the words reservoir and state.

Unlike PerfectIt, BriefCatch and WordRake focus on enhancing concision and readability. With regard to Gorsuch’s opinion in the Texas case, both programs were sparse in their edits. A good example is the first paragraph, which some readers have praised for doing what opening paragraphs should do — draw in the reader.

BriefCatch made two suggested edits to this paragraph. First, it suggested changing “are made” because it is the passive voice. It did not provide rewording, but a sidebar suggested, “[R]ewrite in the active voice, focusing on the actor, not the action.” BriefCatch also suggested changing “In an effort to reconcile” to the more concise “To reconcile.”

WordRake made the same suggestion to shorten “In an effort to” to simply “To,” but it did not pick up on the passive voice.

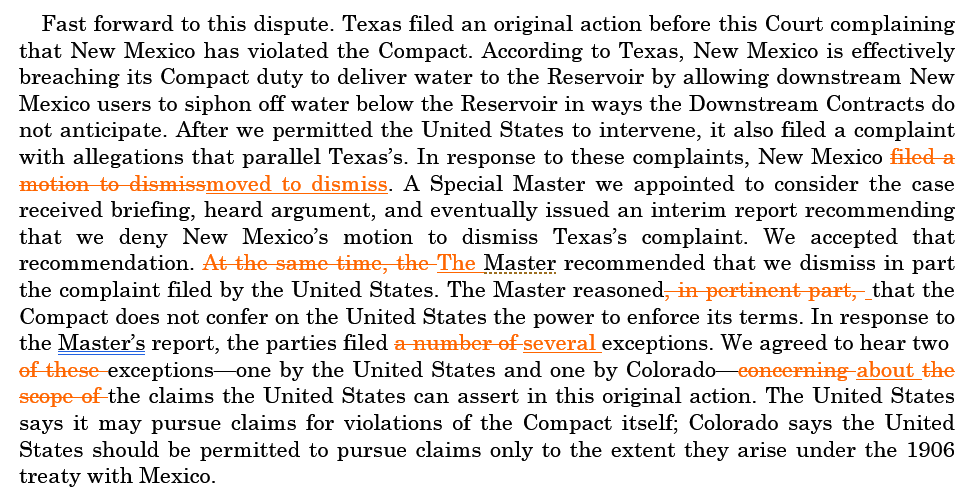

Skipping over the next two paragraphs to the fourth, BriefCatch offered several suggestions. (Note that BriefCatch highlights text and shows the suggestions in a right-hand panel, whereas WordRake shows its suggested edits directly in the document.) BriefCatch suggested changing “before this Court” to “here.” It suggested that the phrase, “New Mexico filed a motion to dismiss,” be changed to “New Mexico moved to dismiss,” explaining that it is better to use “strong verbs” that are “short and sweet.” It recommended deleting “in pertinent part” as unnecessary and changing “a number of” to “many” or “several.” It suggested replacing “concerning” with a shorter word such as “about,” “for,” “over” or “as for.” It also suggested changing “violations of” to “violating,” changing “be permitted” from passive to active voice, and changing “to the extent they” to “if they.”

WordRake made some but not all of the same suggestions. It agreed on changing “filed a motion to dismiss” to “moved to dismiss,” getting rid of “in pertinent part,” changing “a number of” to “several,” and changing “concerning” to “about.” One suggestion it made that BriefCatch did not was to delete the phrase, “At the same time.”

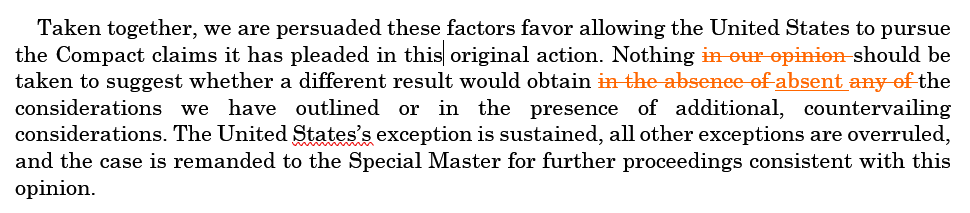

Both BriefCatch and WordRake continued to make similar corrections throughout the opinion. Here is how BriefCatch edited the opinion’s final paragraph. For the phrases “are persuaded,” “be taken,” “is sustained,” “are overruled” and “is remanded,” BriefCatch suggested changing all from the passive to the active voice. It also suggested changing “in the absence of” to “without.”

Both BriefCatch and WordRake continued to make similar corrections throughout the opinion. Here is how BriefCatch edited the opinion’s final paragraph. For the phrases “are persuaded,” “be taken,” “is sustained,” “are overruled” and “is remanded,” BriefCatch suggested changing all from the passive to the active voice. It also suggested changing “in the absence of” to “without.”

WordRake made no mention of the paragraph’s frequent use of the passive voice and suggested a crisper edit to the “absence of” phrase, changing “in the absence of any of the considerations” to “absent the considerations.” It also made the nonsensical suggestion to change “Nothing in our opinion should be taken” to “Nothing should be taken.”

Artis v. District of Columbia

With Gorsuch’s writing in Texas v. New Mexico having come through these editing programs relatively unscathed, I decided to go back to his dissenting opinion in Artis v. District of Columbia. This was the opinion Slate author Mark Joseph Stern cited as an example when he wrote, “Gorsuch’s prose has curdled into a glop of cutesy idioms, pointless metaphors, and garbled diction that’s exhausting to read and impossible to take seriously.”

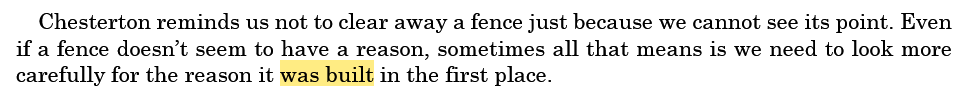

Both BriefCatch and PerfectIt were far kinder. Here again, BriefCatch tended to focus on instances of the passive voice and WordRake tended to look for opportunities to shorten sentences. This is illustrated in the first paragraph of Artis. BriefCatch seized on the passive voice in “was built.”

WordRake tried to shorten the paragraph, with nonsensical results. It wanted to change, “… sometimes all that means is we need to look more carefully for the reason it was built in the first place,” to, “… sometimes all that means is we need to look more carefully it was built.” Huh?

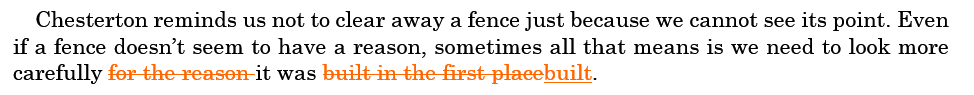

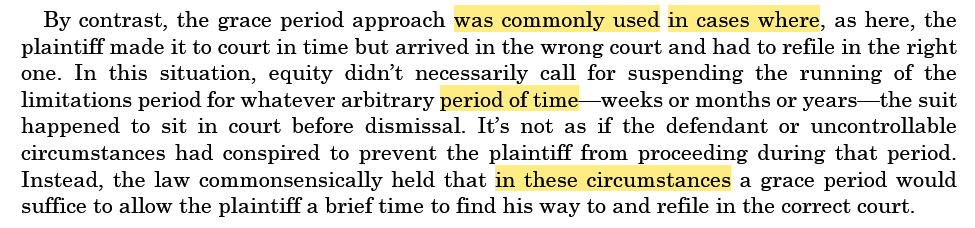

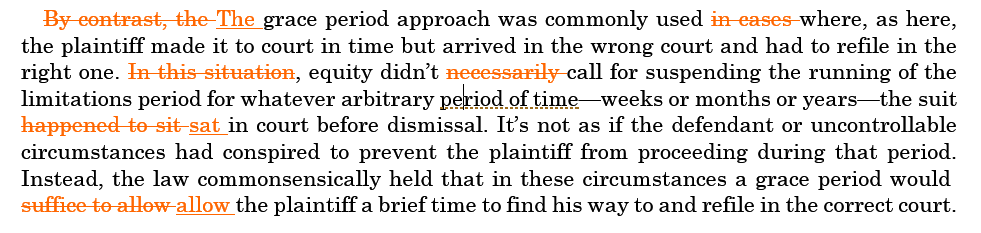

The two programs diverged in this next paragraph. BriefCatch disapproved of the passive “was commonly used” and wanted to change “in cases where” to “when.” It suggested changing “period of time” to either “period” or “time” and “in these circumstances” to “here,” “in that case,” or “in that event.”

WordRake ignored all of BriefCatch’s suggestions. Instead, it deleted the transitional phrases “by contrast” and “in this situation.” It changed “used in cases where” to “used where” and deleted “necessarily.” It changed “happened to sit” to “sat” and “suffice to allow” to “allow.”

The two programs made various other edits to the dissent, but they were all in the same vein and relatively innocuous from a critical perspective.

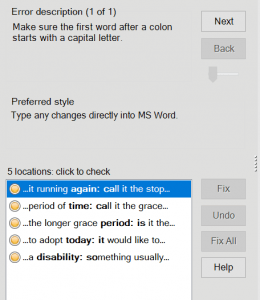

PerfectIt, as I mentioned, performs a unique set of tests. It noted right off that Gorsuch twice failed to hyphenate “common law” in the phrase “common law rule,” and suggested that hyphenation is preferred. It found the same omission in several other phrases, such as “state law claims.” It also found five instances where Gorsuch failed to capitalize the first word after a colon. It found numerous instances where words appeared both capitalized and uncapitalized, such as “Court” and “court” and “State” and “state.”

PerfectIt, as I mentioned, performs a unique set of tests. It noted right off that Gorsuch twice failed to hyphenate “common law” in the phrase “common law rule,” and suggested that hyphenation is preferred. It found the same omission in several other phrases, such as “state law claims.” It also found five instances where Gorsuch failed to capitalize the first word after a colon. It found numerous instances where words appeared both capitalized and uncapitalized, such as “Court” and “court” and “State” and “state.”

Henson v. Santander

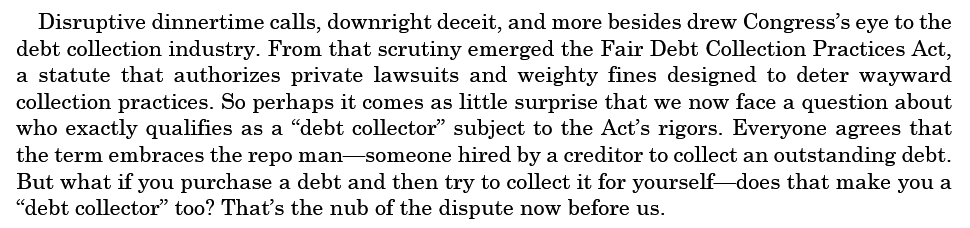

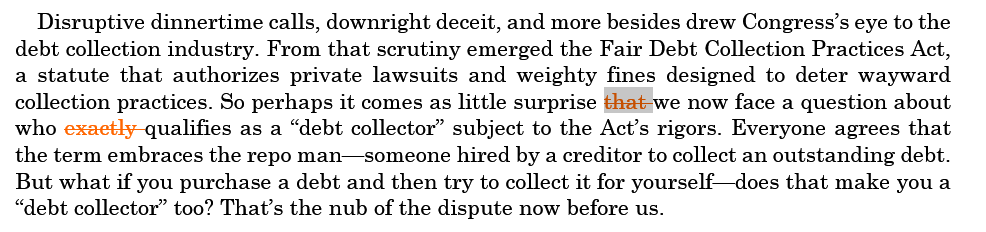

Rather than continue with Artis, I decided to turn to a paragraph that has generated much critical comment, both favorable and disfavorable. It is the first paragraph in Gorsuch’s first majority opinion since joining the Supreme Court, Henson v. Santander. Scholar Varsava called its alliteration “showy and jarring.”

BriefCatch had no problem with the paragraph.

WordRake suggested two minor changes, deleting “that” and “exactly.”

Thus, neither BriefCatch nor WordRake were bothered by the justice’s showy alliteration.

Reading Happiness

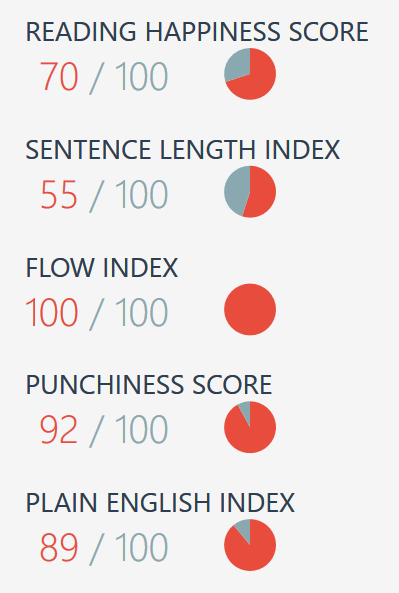

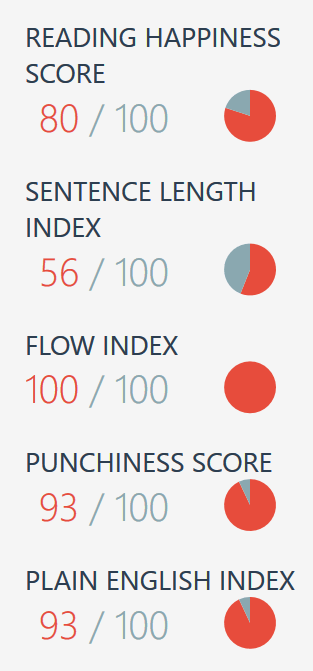

BriefCatch provides two additional analyses that neither WordRake nor PerfectIt have. One is a set of five scores related to readability. (See this explanation.) Here is how Gorsuch scored in the Texas case:

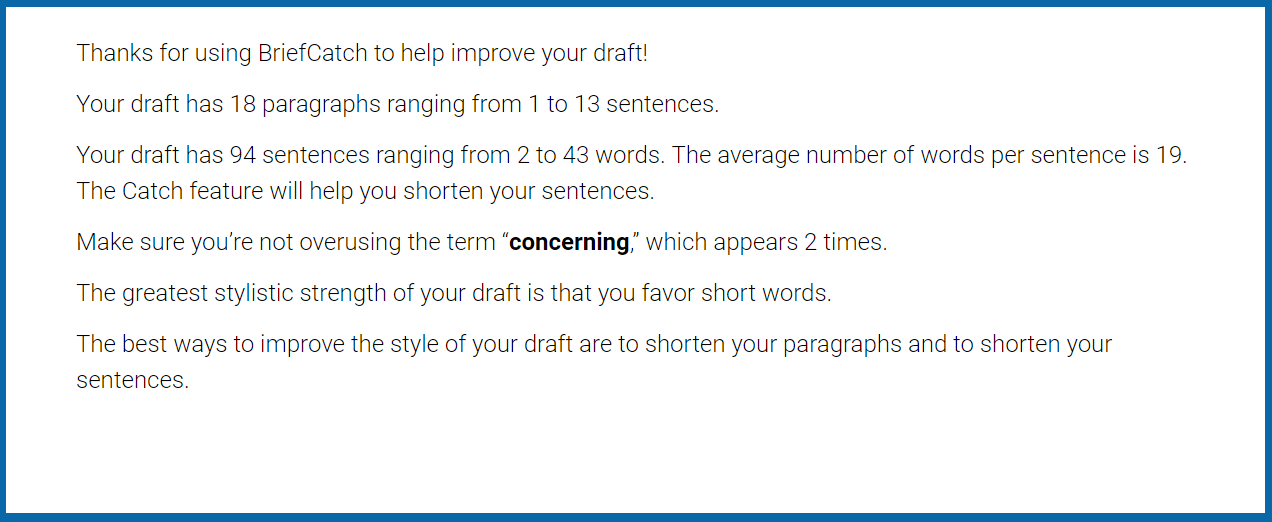

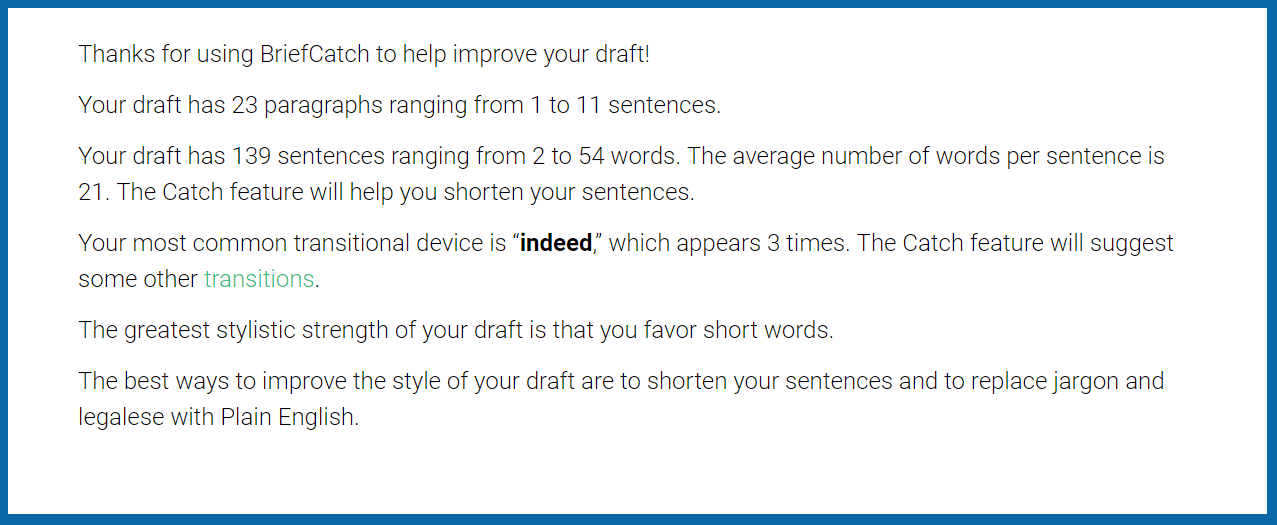

BriefCatch also provides a narrative report. Here was the report for the Texas case:

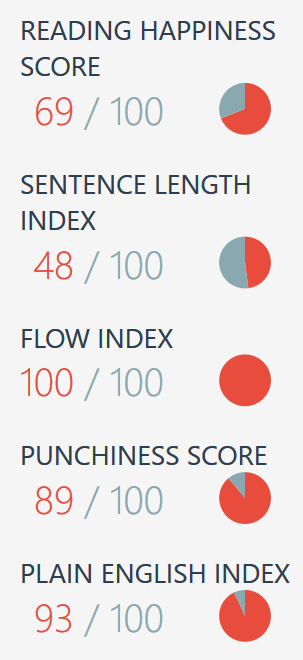

In the Artis dissent — the case Slate criticized — BriefCatch gave him a higher score than in the Texas case:

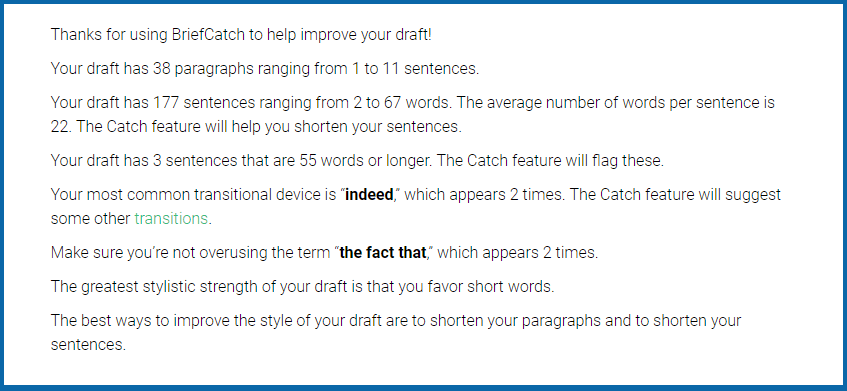

And here was the narrative BriefCatch gave for the Artis dissent:

In Henson, the opinion with the “showy” alliteration, BriefCatch gave Gorsuch the lowest overall score of the three opinions:

And here is the narrative it provided for Henson:

The Bottom Line

I performed this analysis in order to compare how different legal editing programs would handle the same documents. As you can see, PerfectIt is best used as a proofreader and best deployed before finalizing a document to check for errors and inconsistencies. Both BriefCatch and WordRake are also best used before finalizing a document, but for the purpose of tightening language and improving readability.

Use of all of these has to be guided by your own editorial judgment. Just because a program says you should do something, that doesn’t always mean you should. Otherwise, you might end up with a phrase in your document such as, “We need to look more carefully it was built.”

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog