A federal judge in Georgia has ordered Public Resource to remove Georgia’s official statutes from its website, finding that the state of Georgia holds a valid copyright in them and that Public Resource’s publication was not fair use.

This is the second loss this year for Public Resource in its efforts to make primary legal materials freely available to the public. In February, a federal court issued an injunction barring Public Resource from publishing technical and scientific standards incorporated by reference in the Code of Federal Regulations. (See: In Blow to Open Law, Court Upholds Private Copyright in Public Safety Laws.)

At issue in this latest case was the Official Code of Georgia Annotated, which is designated by the Georgia legislature as the official version of the state’s laws. The Georgia Code Revision Commission contracts with LexisNexis to publish the OCGA. Pursuant to that agreement, LexisNexis adds annotations, editorial notes, cross-references, research references and other enhancements.

LexisNexis sells the OCGA for $395. It publishes an online version that is free, but that omits the annotations.

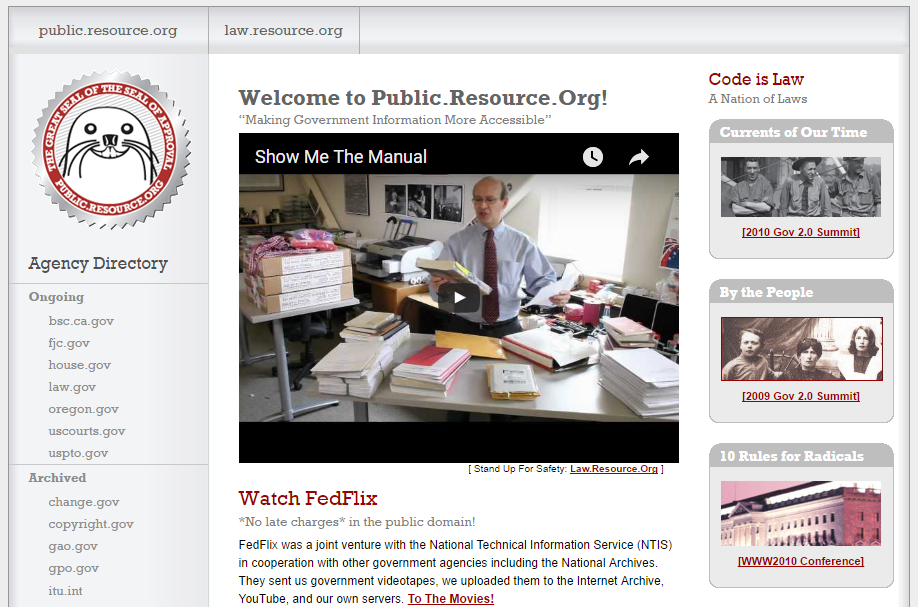

In 2013, Carl Malamud, CEO of Public Resource, paid $1,207.02 to purchase the entire print set of the OCGA. He then scanned the set and posted it to his site. He also sent copies on thumb drives to various Georgia legislative officials. Soon thereafter, the chair of the Georgia Code Revision Commission sent Malamud a take-down demand. When Malamud refused, the Georgia legislature the commission filed suit in federal court in Atlanta.

Malamud defended his publication on two grounds. First, he argued that the OCGA could not be copyrighted because of the unusual circumstances in Georgia by which the annotated version is also the official version. Second, he argued that, even if the OCGA is copyrightable, his publication was fair use.

In an opinion issued March 23, U.S. District Judge Richard W. Story disagreed on both arguments.

On the copyright question, Story held that a long line of cases recognizes copyright protection for annotated cases and statutes. The unusual circumstances here do not change that, he said.

The Court acknowledges that this is an unusual case because most official codes are not annotated and most annotated codes are not official. The annotations here are nonetheless entitled to copyright protection. The Court finds that Callaghan v. Mvers. 128 U.S. 617 (1888), in which the Court found annotations in a legal reporter were copyrightable by the publisher, is instructive. Defendant itself has admitted that annotations in an unofficial reporter would be copyrightable, and the Court finds that the Agreement does not transform copyrightable material into non-copyrightable material.

On fair use, Story conducted a multi-part analysis to conclude that Malamud’s publication was not fair use. Interestingly, as part of that analysis, Story found that Public Resource’s use was not for a “nonprofit educational purpose” but for a “commercial purpose.”

Public Resource is a non-profit and does not sell access to the materials it publishes. But the judge found it was commercial nonetheless.

In this case. Defendant’s business involves copying and providing what it deems to be “primary legal materials” on the Internet. Defendant is paid in the form of grants and contributions to further its practice of copying and distributing copyrighted materials. Defendant has also published documents that teach others how to take similar actions with respect to government documents. Therefore, the Court finds that Defendant “profits” by the attention, recognition, and contributions it receives in association with its copying and distributing the copyrighted O.C.G.A. annotations, and its use was neither nonprofit nor educational.

The full opinion is available — where else? — at the Public Resource site.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog